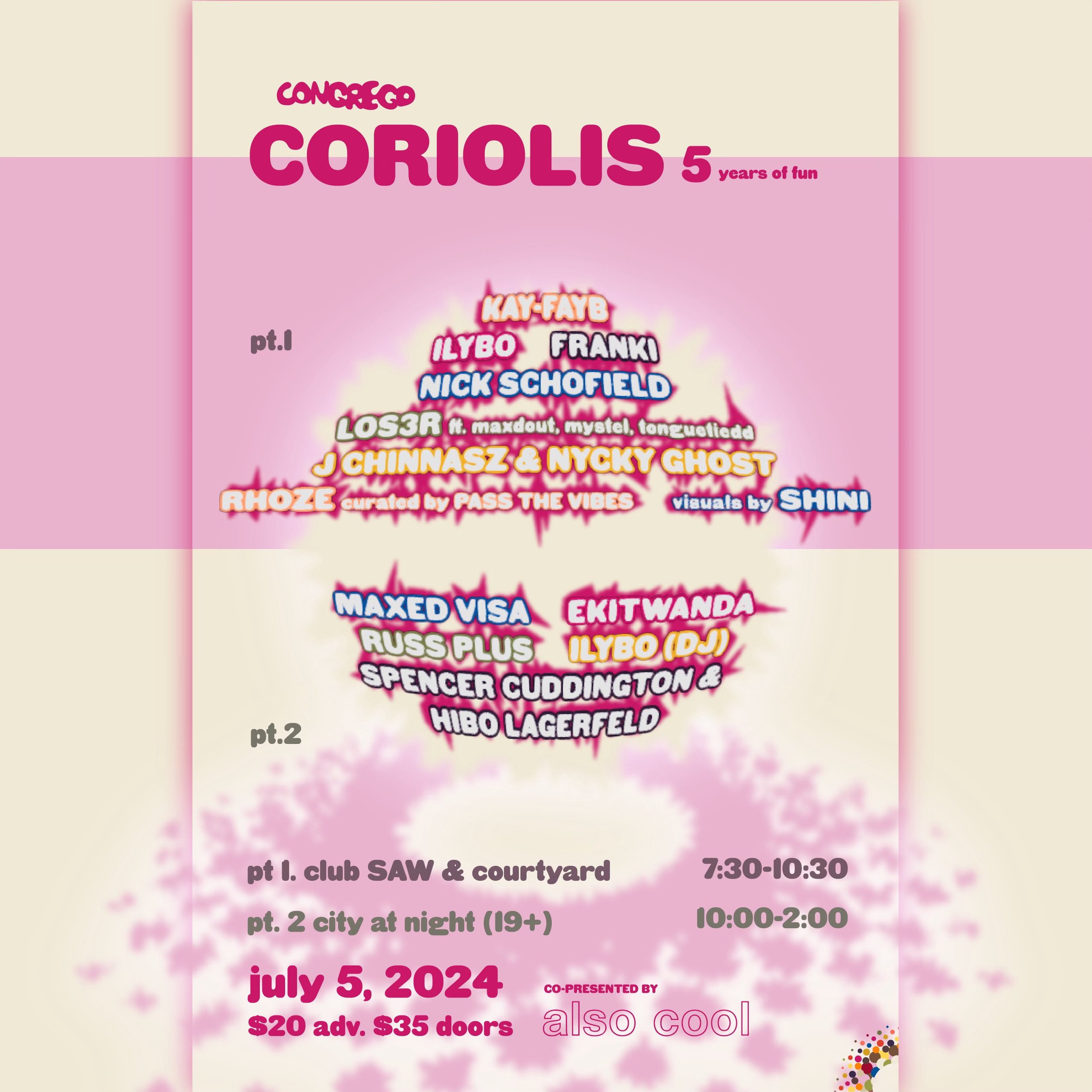

Twelve Vacancies 2025: The Festival that Made it Out of the Group Chat

The Twelve Vacancies team by Judy Yun (not pictured: Kaya Davies)

A year and a half ago, McGill students Amelia McCluskey, Marina Marshall, and Kaya Davies were in a group chat discussing the lack of a film community at their university. When McCluskey sent a text about how cool it would be if they started their own festival, the group of friends put the idea in motion and established Twelve Vacancies: a non-profit experimental and horror short film festival that takes place at McGill.

Devoted horror heads may recognize the name of the festival, chosen by Assistant Coordinator Gabrielle Cole, from Alfred Hitchcock’s hit film Psycho (1960), which is often hailed as one of the best horror films of all time. Coincidentally, the past two editions of the festival screened 12 films each, which is the number of vacant cabins at the infamous Bates Motel. Although the 2025 edition of Twelve Vacancies featured 14 films, the horror homage prepares patrons for the impending eeriness of the night. In addition to the spotlight on horror—a genre that the team says is underrated and over-hated by film festivals—all of the films screened are experimental in medium, style, content, or oftentimes, all of the above.

Twelve Vacancies’ third edition took place on March 20th and 21st at the Peel Street Cinema, a McGill classroom/theatre tucked away in a 19th-century townhouse on campus. Although the festival began as one night, an additional night was added this time around in response to how quickly the first two editions sold out. Some hopeful attendees messaged the festival’s Instagram last time after realizing tickets were gone, even offering to sit on the floor if it meant they got to go, testifying to the demand for affordable, entertaining events like this.

With not a single empty seat in the house, festival-goers settled into their plush theatre chairs, flipped through the glossy programs, and snacked on complimentary popcorn while eagerly awaiting the start of the show. The night kicked off with a brief speech from Festival Coordinator McCluskey, who thanked everyone for being there and shouted out the filmmakers in attendance. She also expressed gratitude for her mother Claire Robertson, the artist behind the charming red-eyed cat logo that can be found on everything Twelve Vacancies.

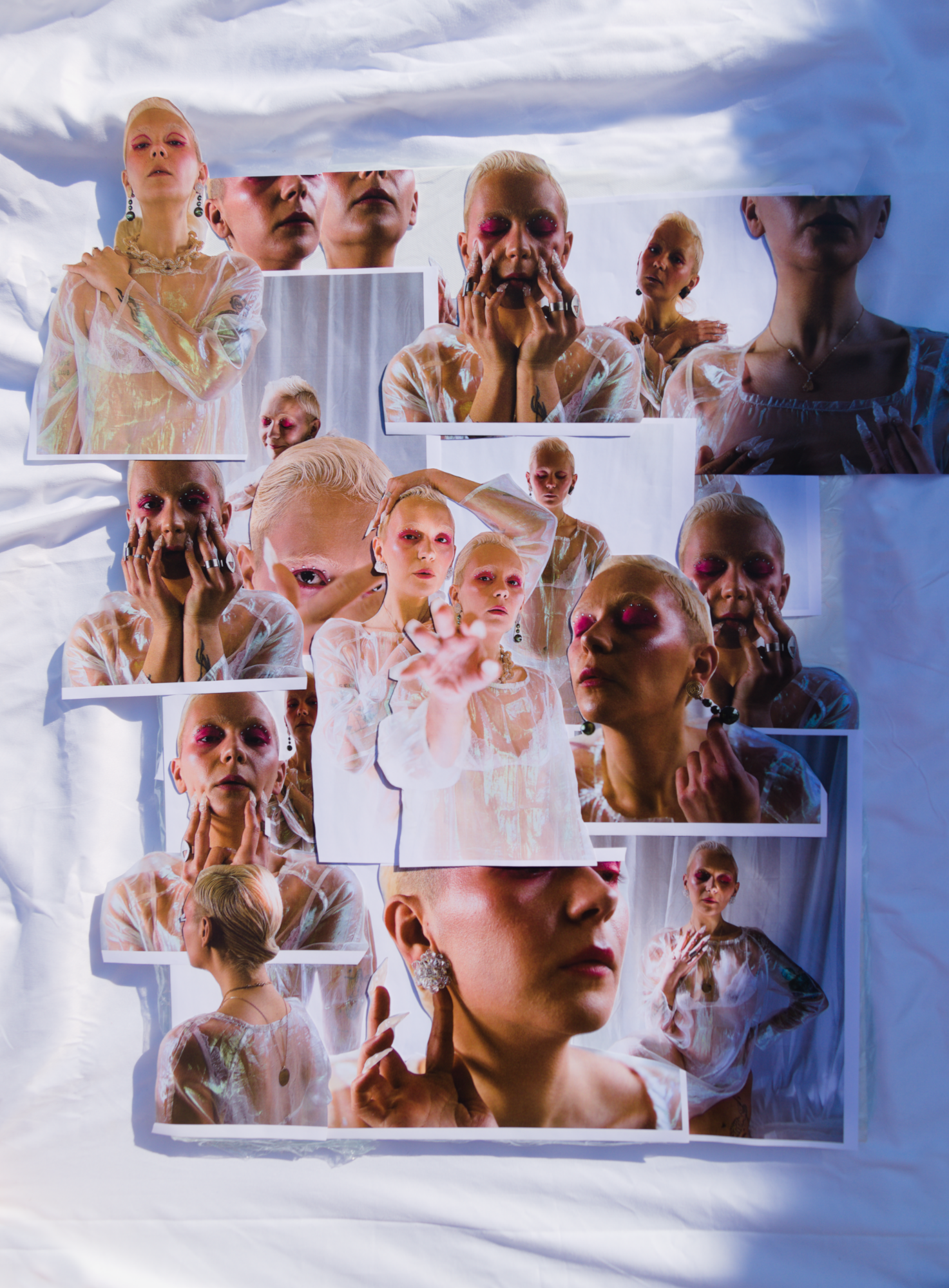

Photo by Judy Yun

The first seven films screened were a blend of eccentric animations, hallucinatory live-action, and nostalgia-fueled stop motion. This was followed by a brief intermission in which audience members mingled, grabbed more popcorn, and purchased glistening stickers designed by Elias Doering and Kaya Davies. The uncanny madness continued into the second half, which featured an all-consuming itch that just won’t quit, homoerotic skeletons, and carefully-crafted body horror.

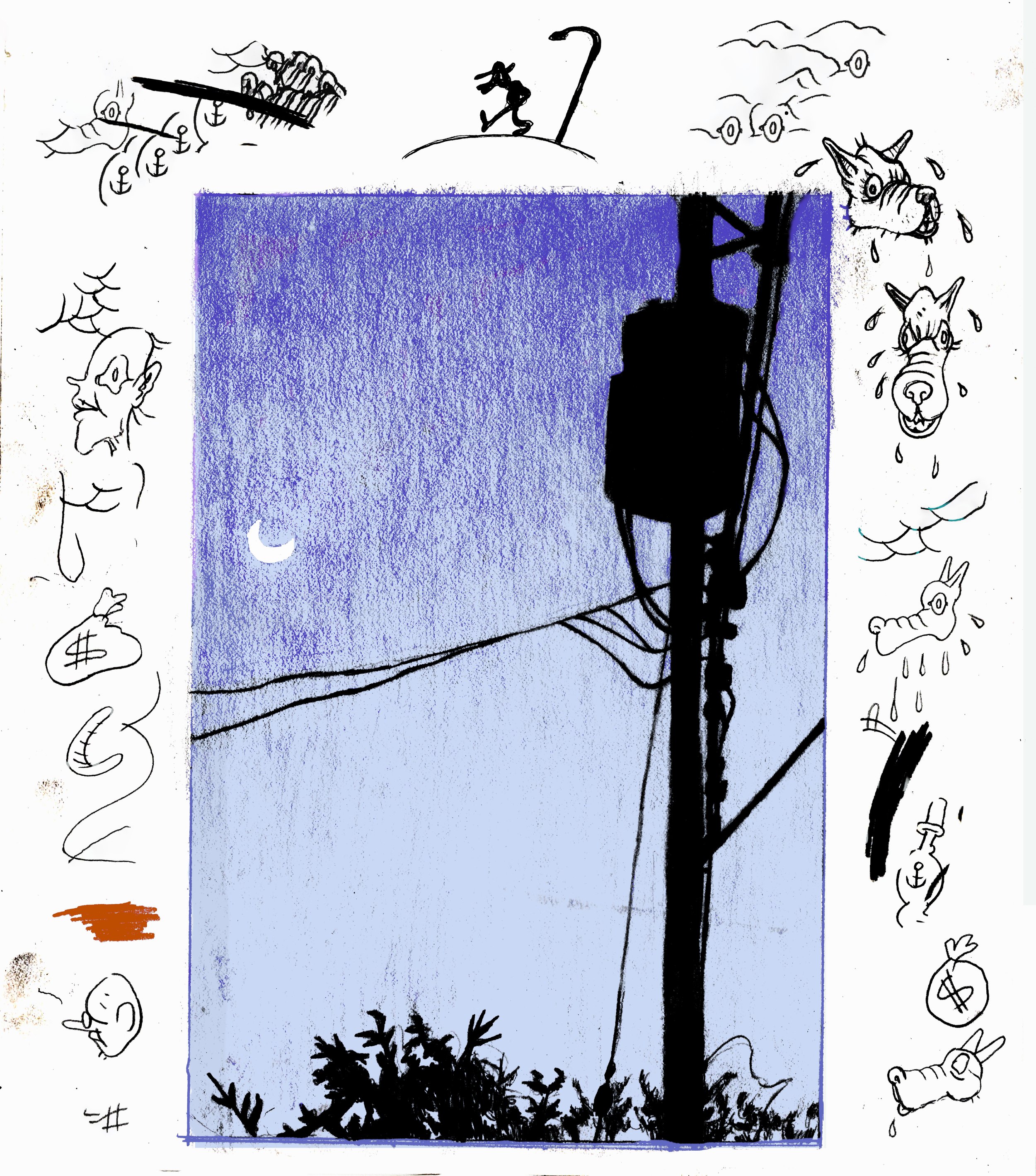

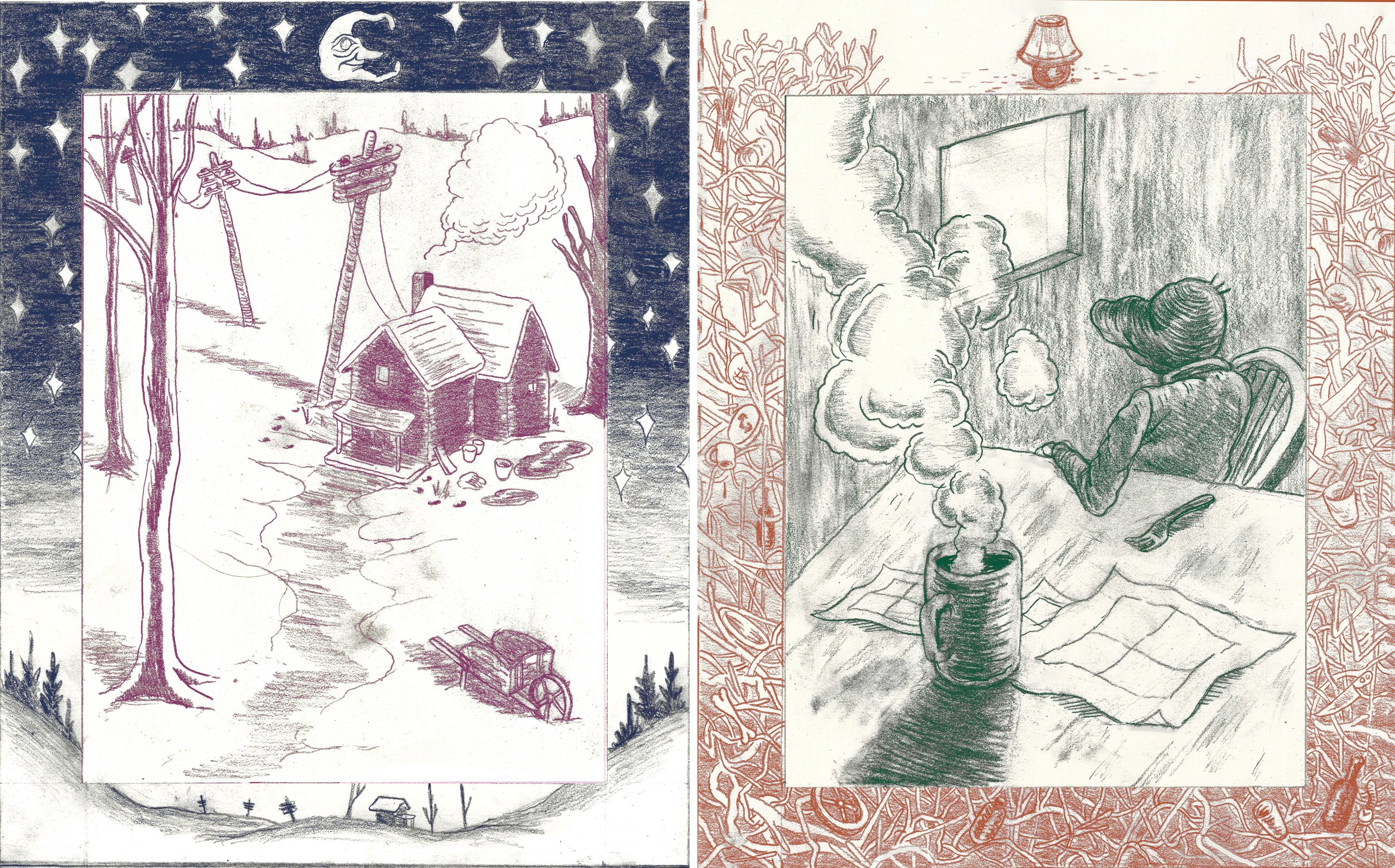

My Friend in the Jingle Truck (2025) by Sima Naseem

At the end of both nights, the audience was invited to vote for their favourite film, a nearly impossible task considering all of the talent on display. The Fan Favourite Award went to My Friend in the Jingle Truck (2025), a mixed media journey of a young Pakistani girl into the whimsical, animal-filled world contained within a painting on the side of a truck. Masterfully combining textile stop-motion with dreamy, vibrant animation, it’s no surprise that director Sima Naseem captured the audience’s hearts.

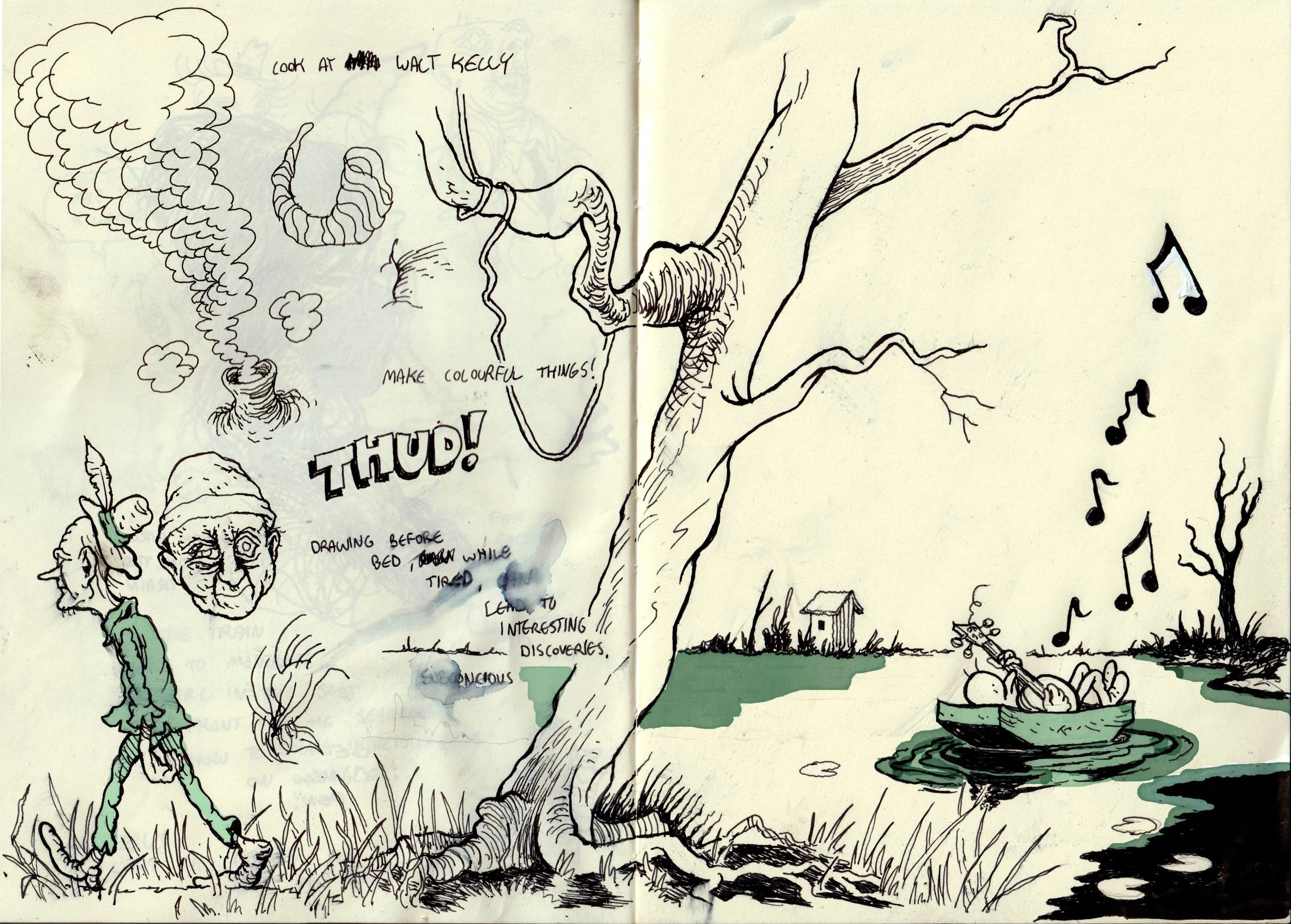

Razor Ruckus (2025) by APPi

In addition to the Fan Favourite Award, the festival introduced a Jury’s Choice Award this year. It was awarded to Razor Ruckus (2025), by APPi, a colourfully animated film detailing the agonizing adventure of a young woman named Gorbe trying to turn off an electric razor gone rogue. The short culminates with the razor hitting Gorbe on her head after an attempt to dispose of it in the river by her apartment, followed by a playful yet pertinent message about littering.

For the first two editions of the festival, the six jury members would get together to watch and discuss all the submissions together in one sitting. However, the recent edition drew in a whopping 103 submissions, equivalent to around eight hours of footage, so they divided the films amongst themselves and selected ones they saw potential in. Despite no longer being able to view all the submissions together, the selection process retains its collaborative nature, resembling a conversation between good friends rather than a heated debate.

In addition to offering viewers an unforgettable night at the cinema, Twelve Vacancies also grants burgeoning filmmakers the opportunity to display their creations in front of a welcoming audience. McCluskey recently attended the Montreal premiere of Universal Language (2024), where she had the opportunity to hear director Matthew Rankin discuss the importance of prospective feature filmmakers having a collection of short films under their belt. Since funding for the arts is scarce, if filmmakers want to make feature films, it is valuable for them to create short films that have been screened at festivals in order to secure funding for a feature debut. At Twelve Vacancies, submissions are accepted from Canadian filmmakers who are either under 25 years old or students, providing an avenue for up-and-coming artists to showcase their work.

While Twelve Vacancies takes place at a university, and is run by a group of friends who met in university, they have never limited themselves to the McGill bubble. With a public page on FilmFreeway, a website where filmmakers can submit their films to hundreds of different festivals, submissions are drawn in from across the country. The team also recently secured a promotional partnership with Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival, the largest genre film festival in North America.

Since everyone on the team will have graduated from McGill at the end of this semester, there is a possibility of expanding beyond Montreal, as several of the members happen to be relocating to Vancouver. Although the future of the festival may be uncertain at the moment, with a growing social media following that has doubled just this past semester, plentiful submissions, and a loyal audience that has sold out every edition, Twelve Vacancies is determined to build upon this momentum and keep the weirdness going for years to come.

Twelve Vacancies

Amelia McCluskey - Festival Coordinator & Jury Member

Gabrielle Cole - Assistant Coordinator & Jury Member

Marina Marshall - Assistant Coordinator & Jury Member

Kaya Davies - Jury Member & Promotional Design

Liam Foese - Jury Member

May Galligan - Jury Member

Zack Steine - Web Design & Tech Support

Twelve Vacancies

Website | Instagram | FilmFreeway

Maggie Caroddo (they/them) is a lesbian writer and film fanatic originally from Long Island/Lenape Land and currently based in Montréal/Tiohtià:ke. You can check out more of their work here.