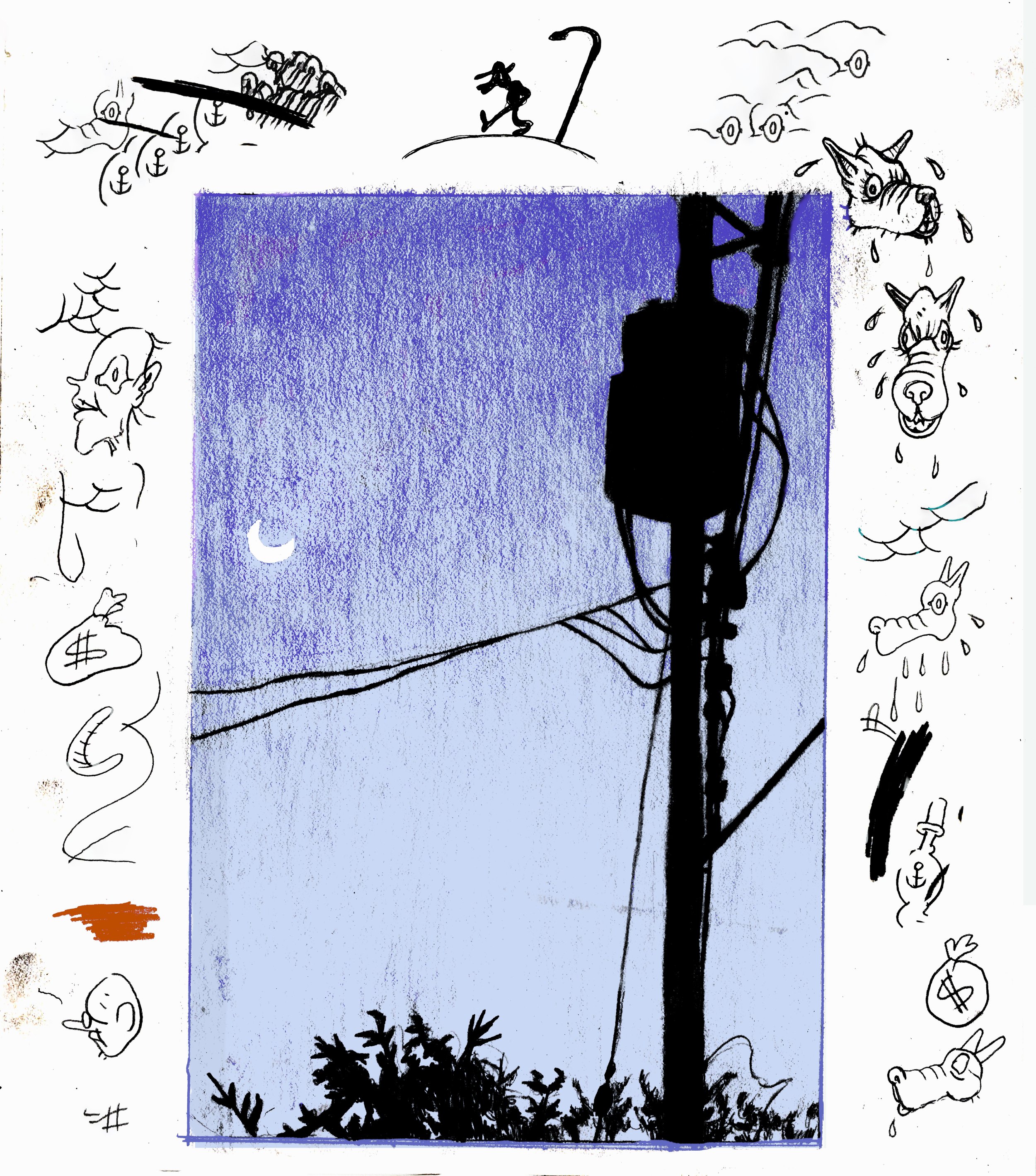

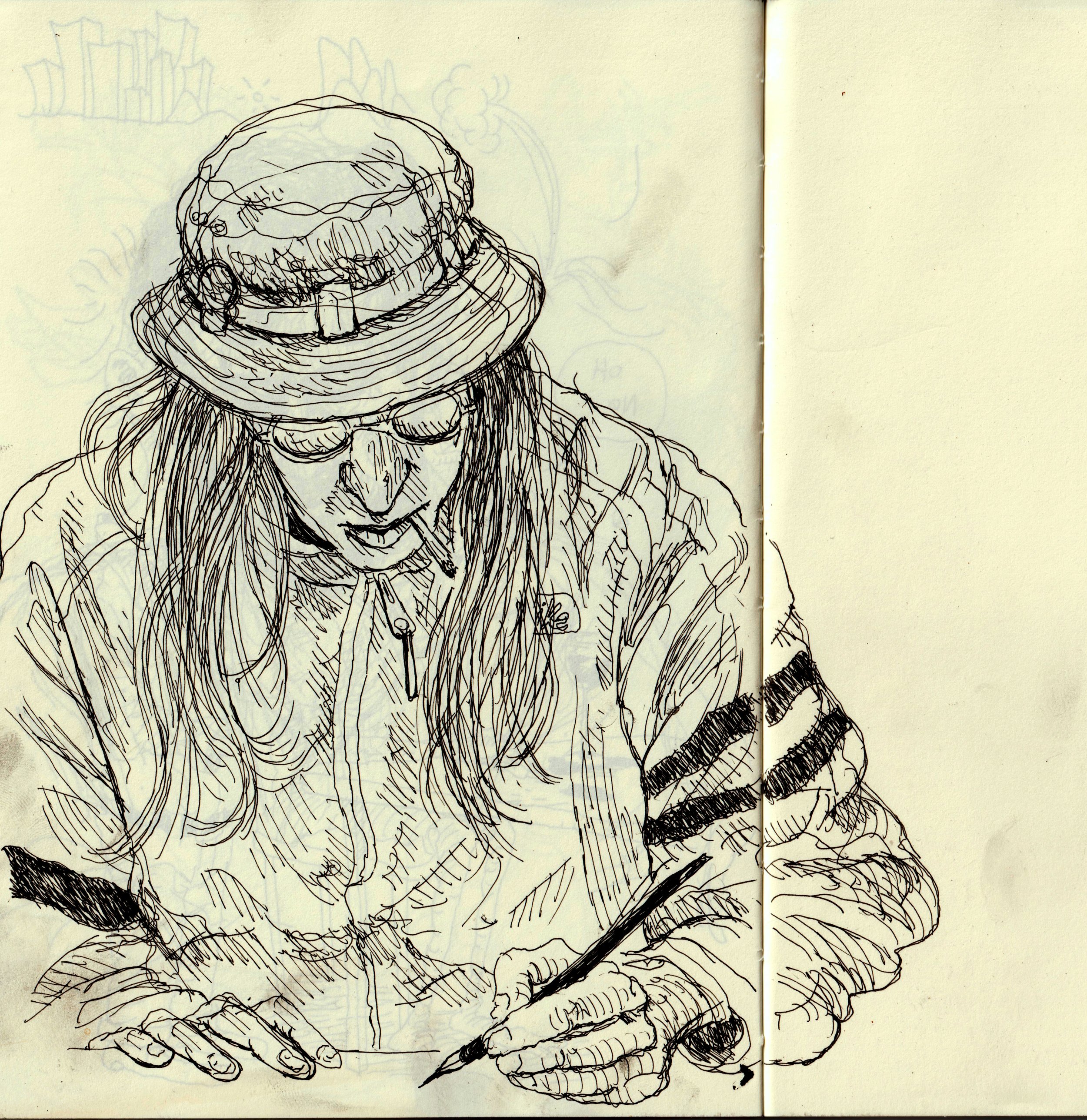

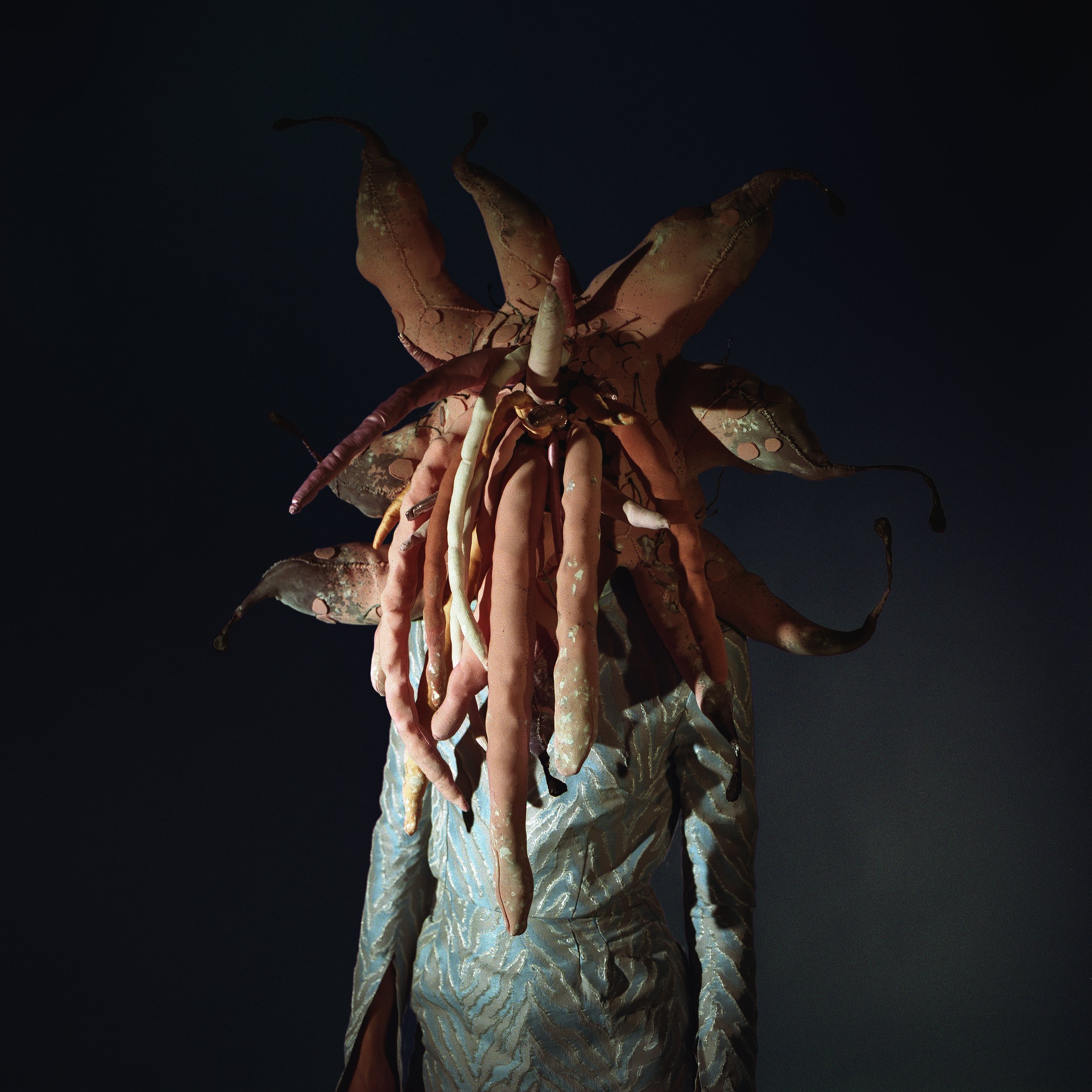

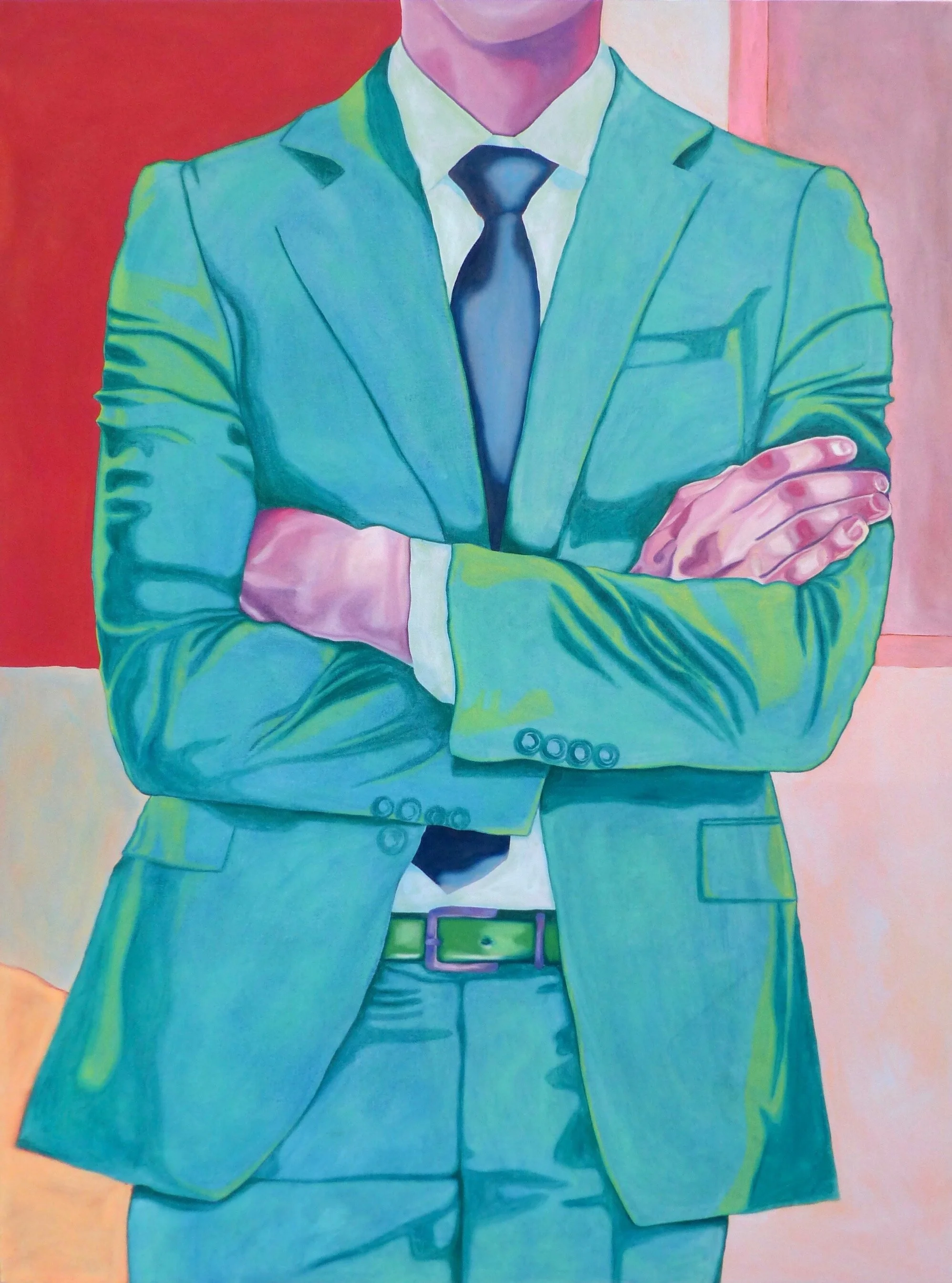

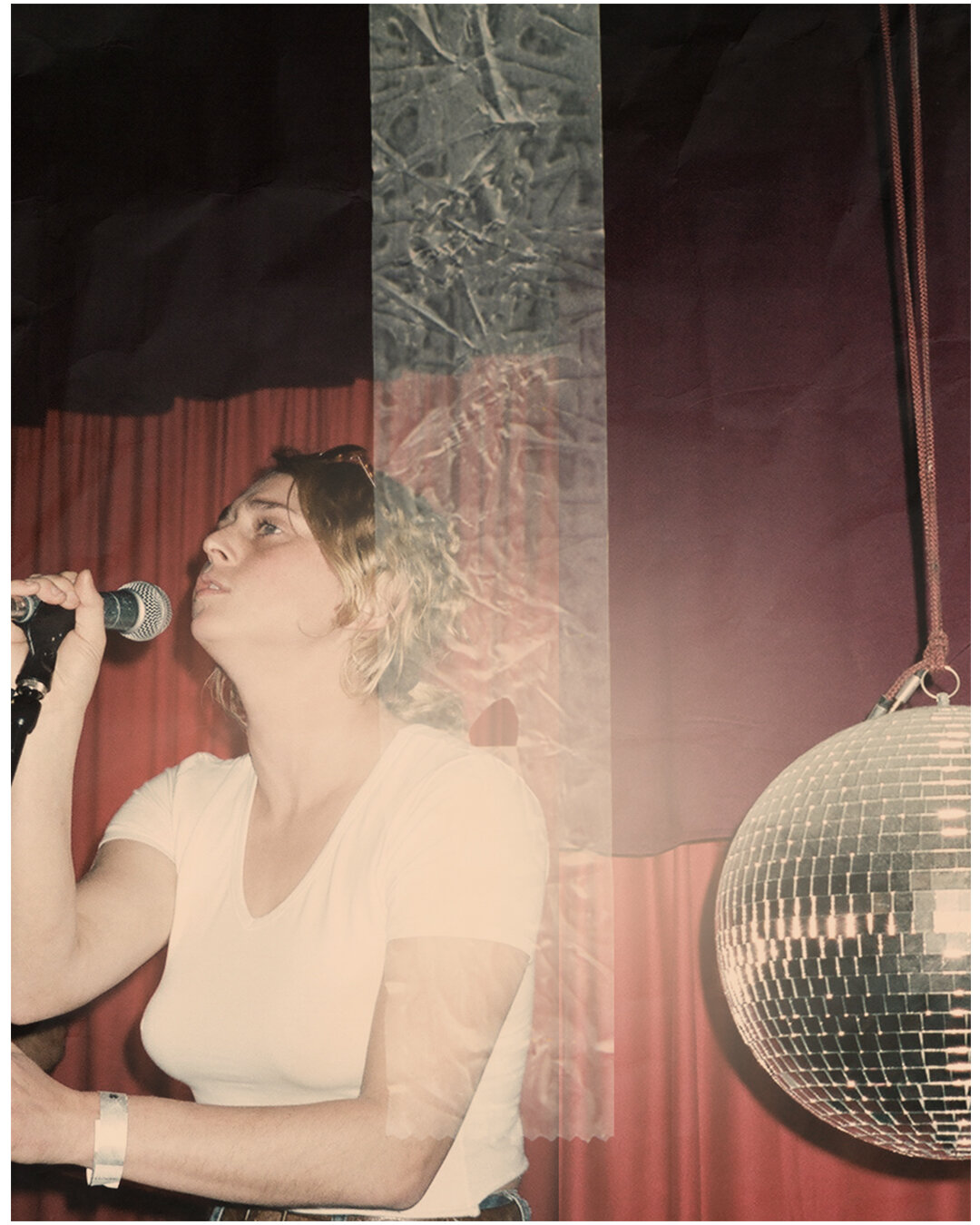

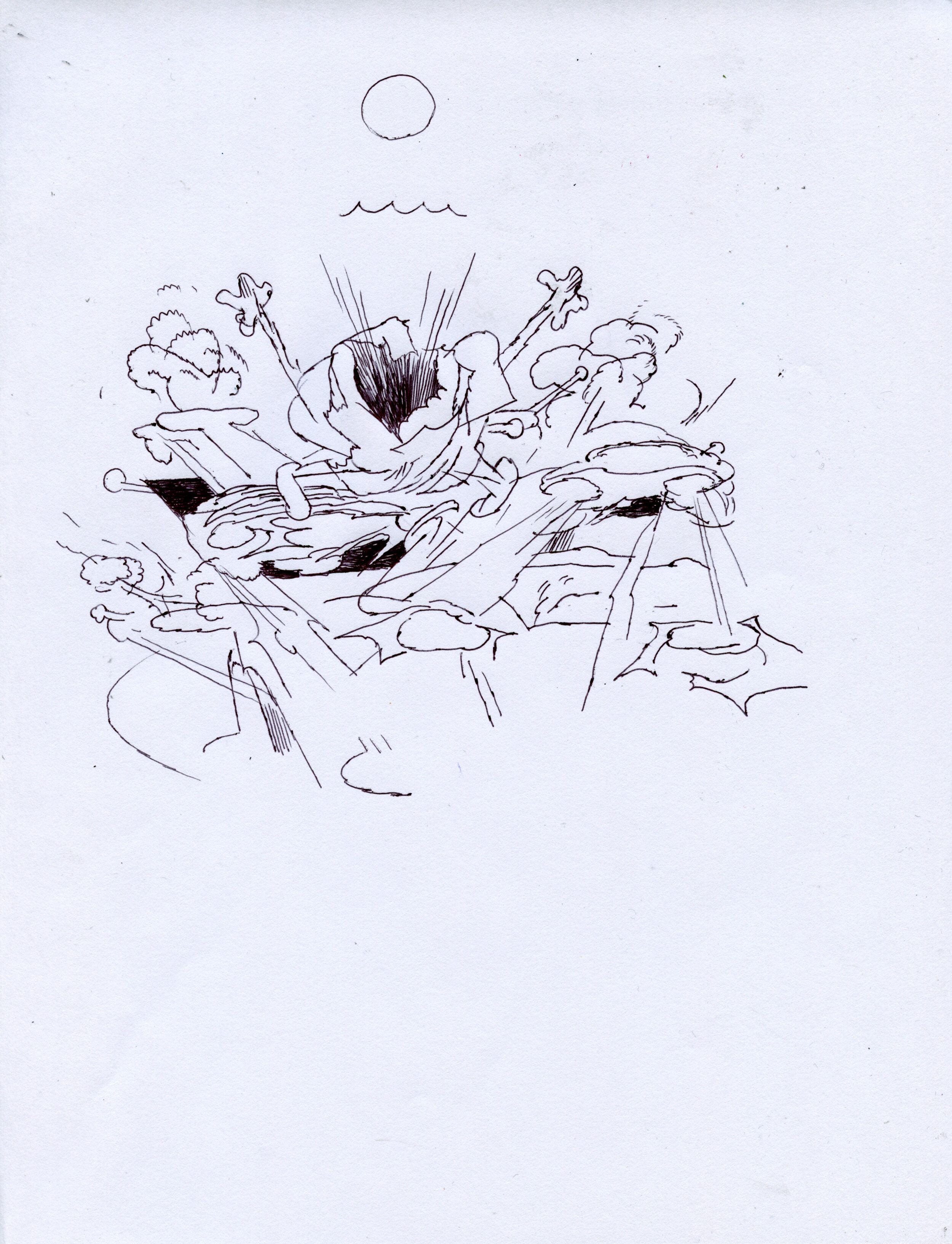

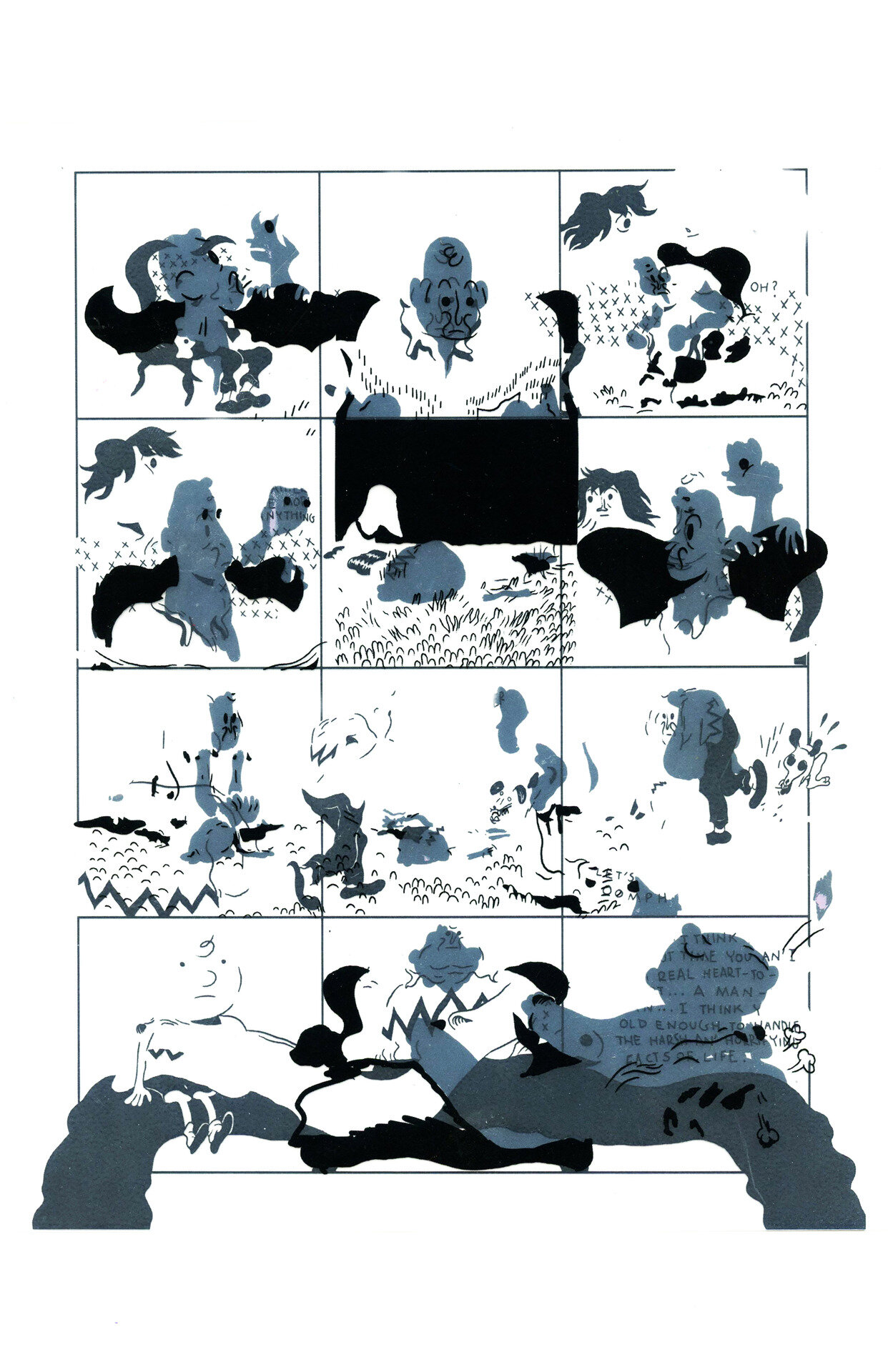

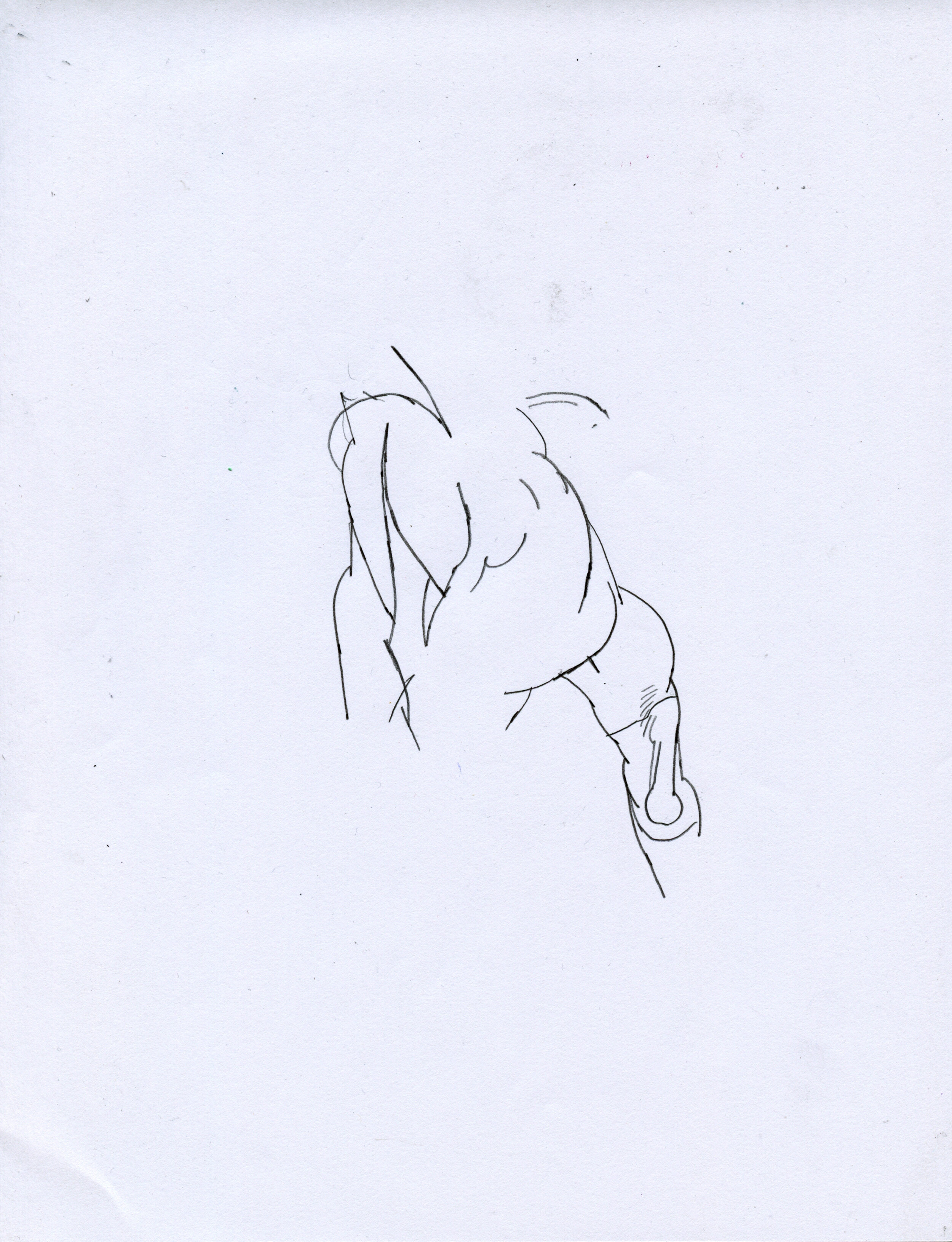

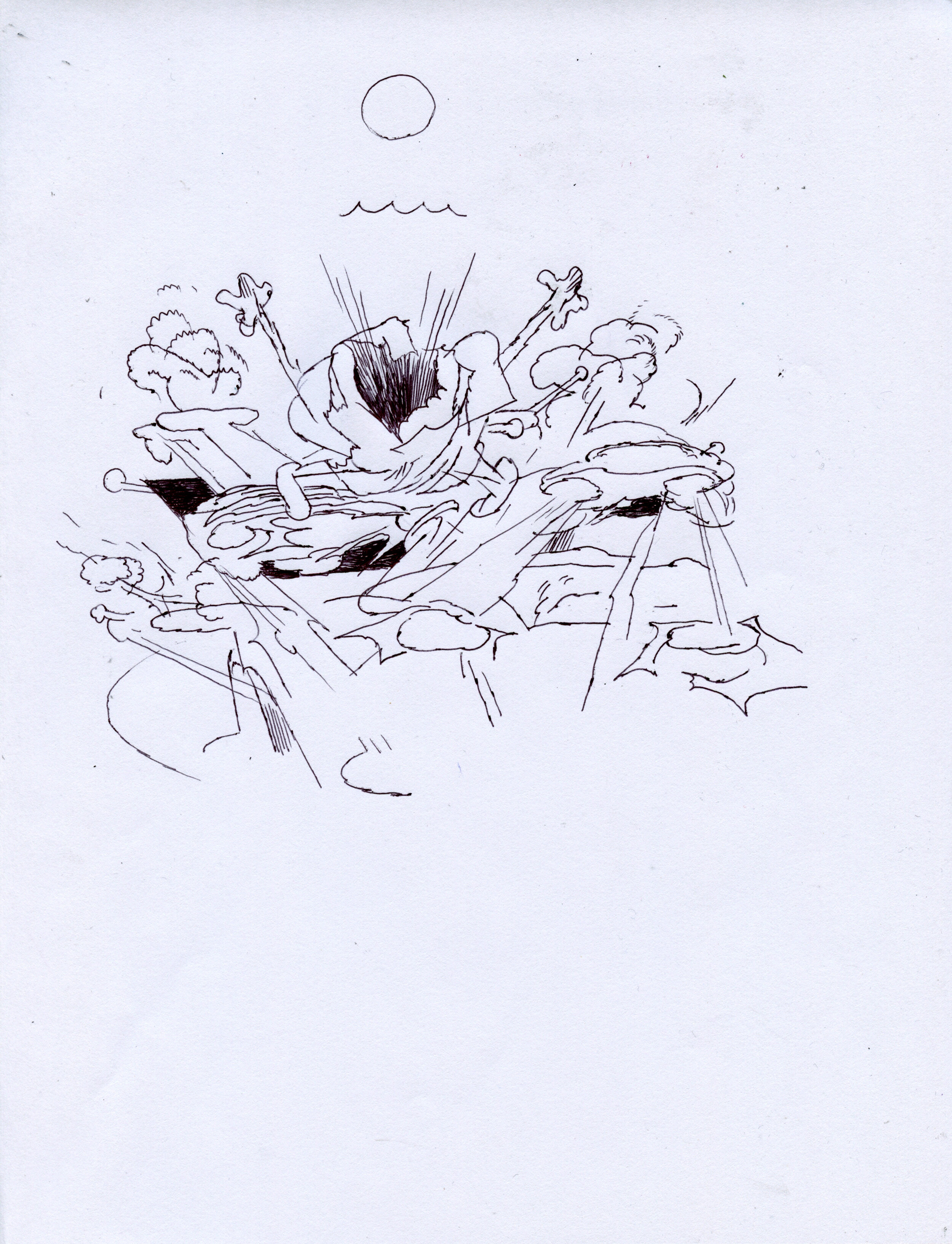

Artist Spotlight: James Collier

Art by James Collier

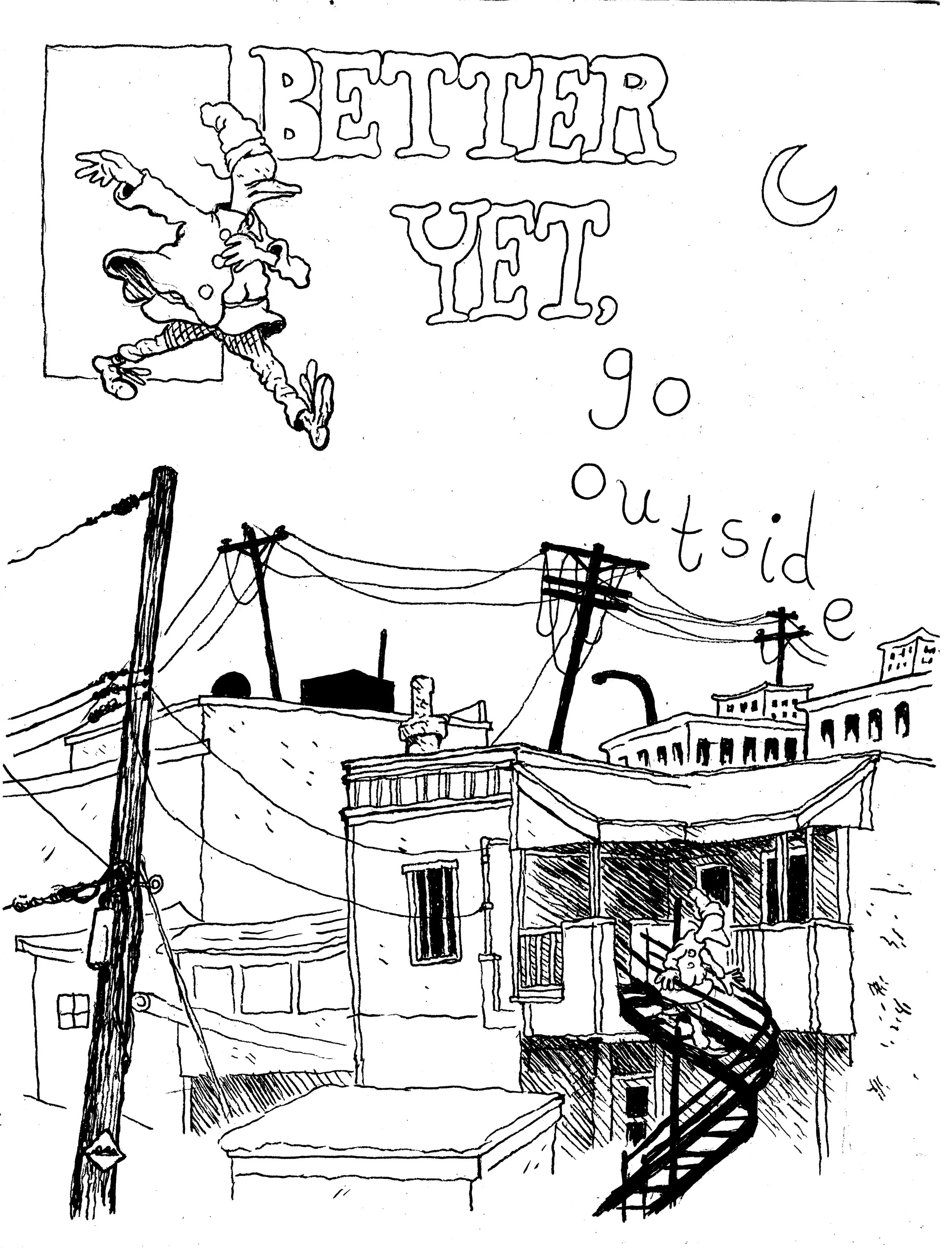

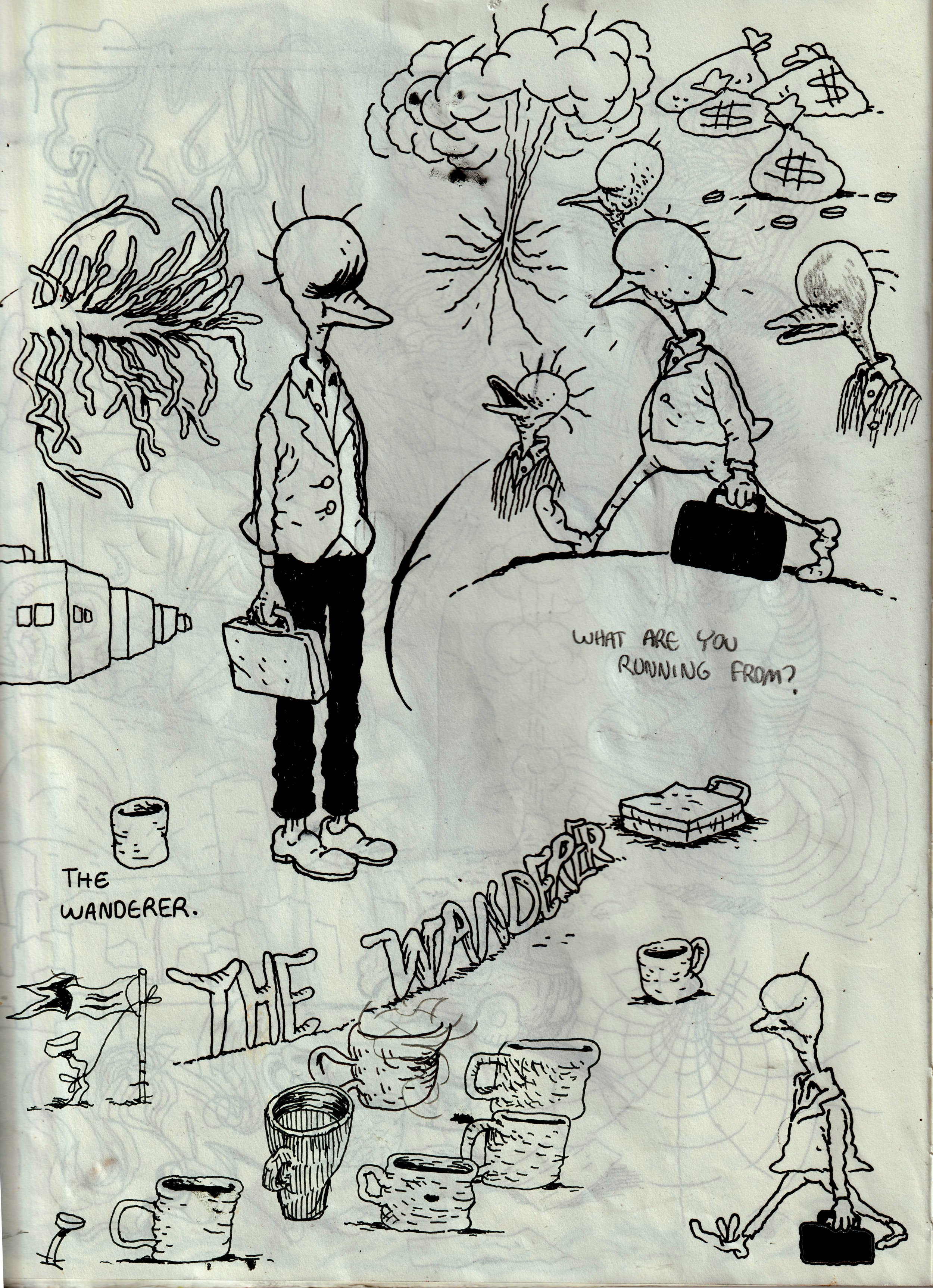

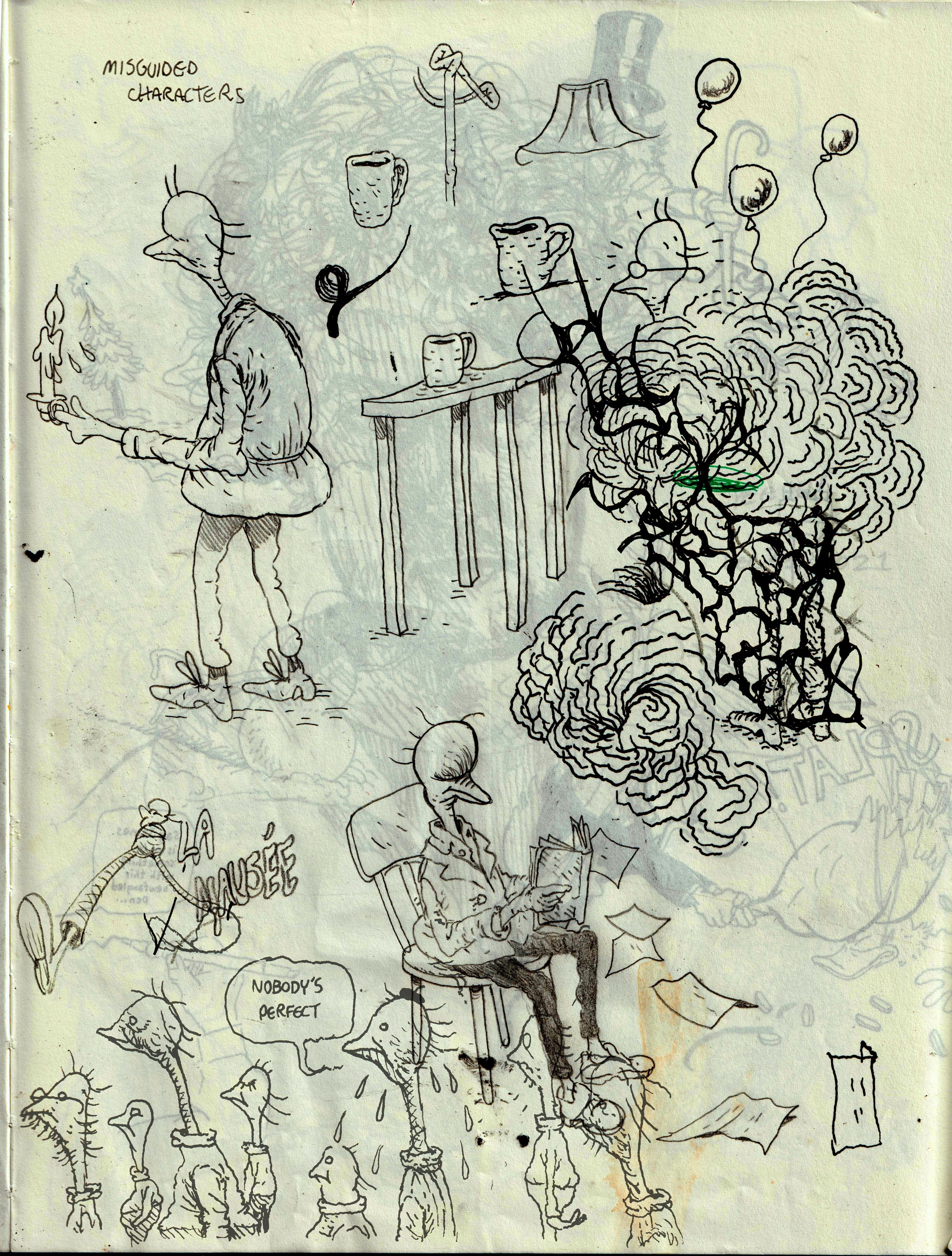

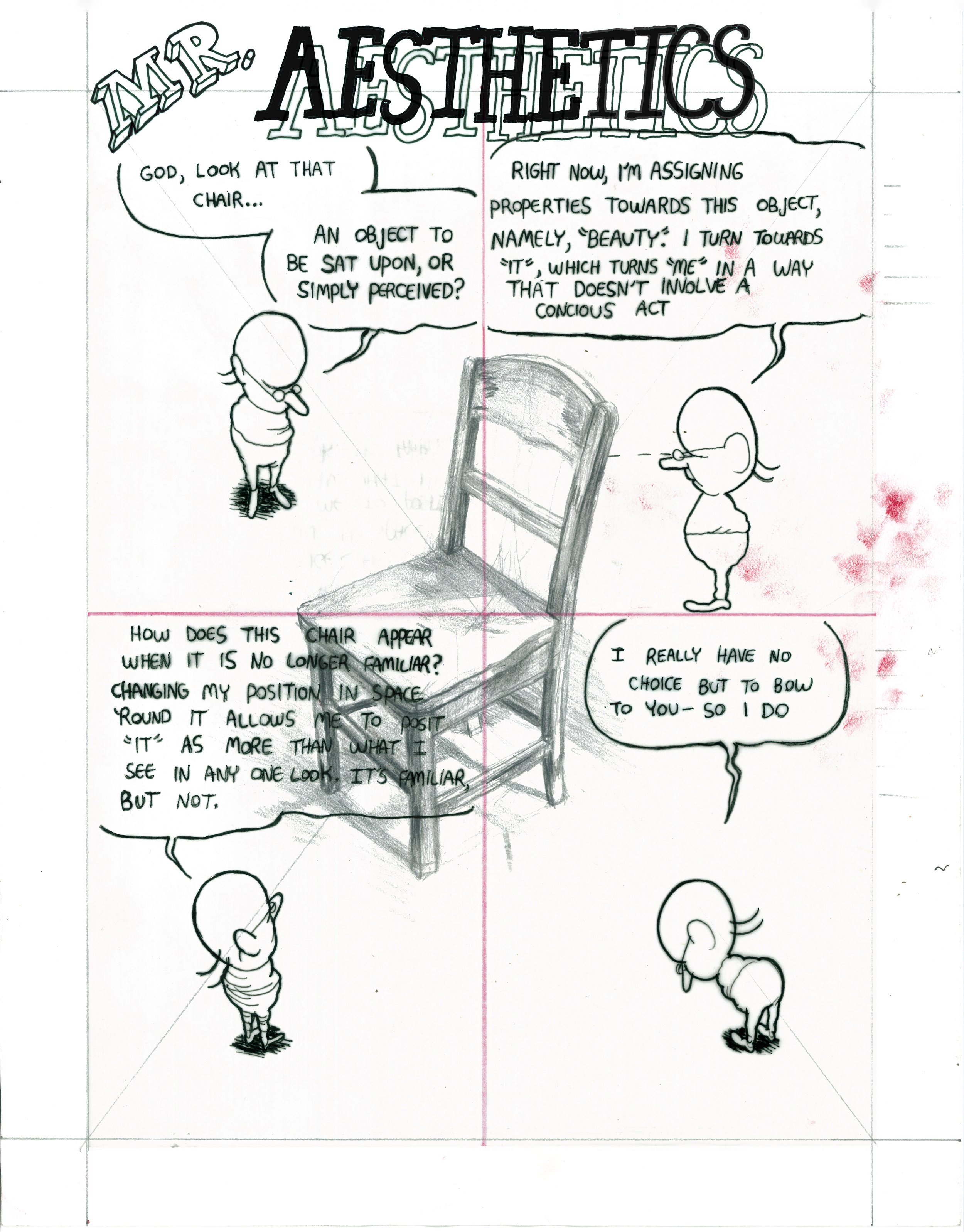

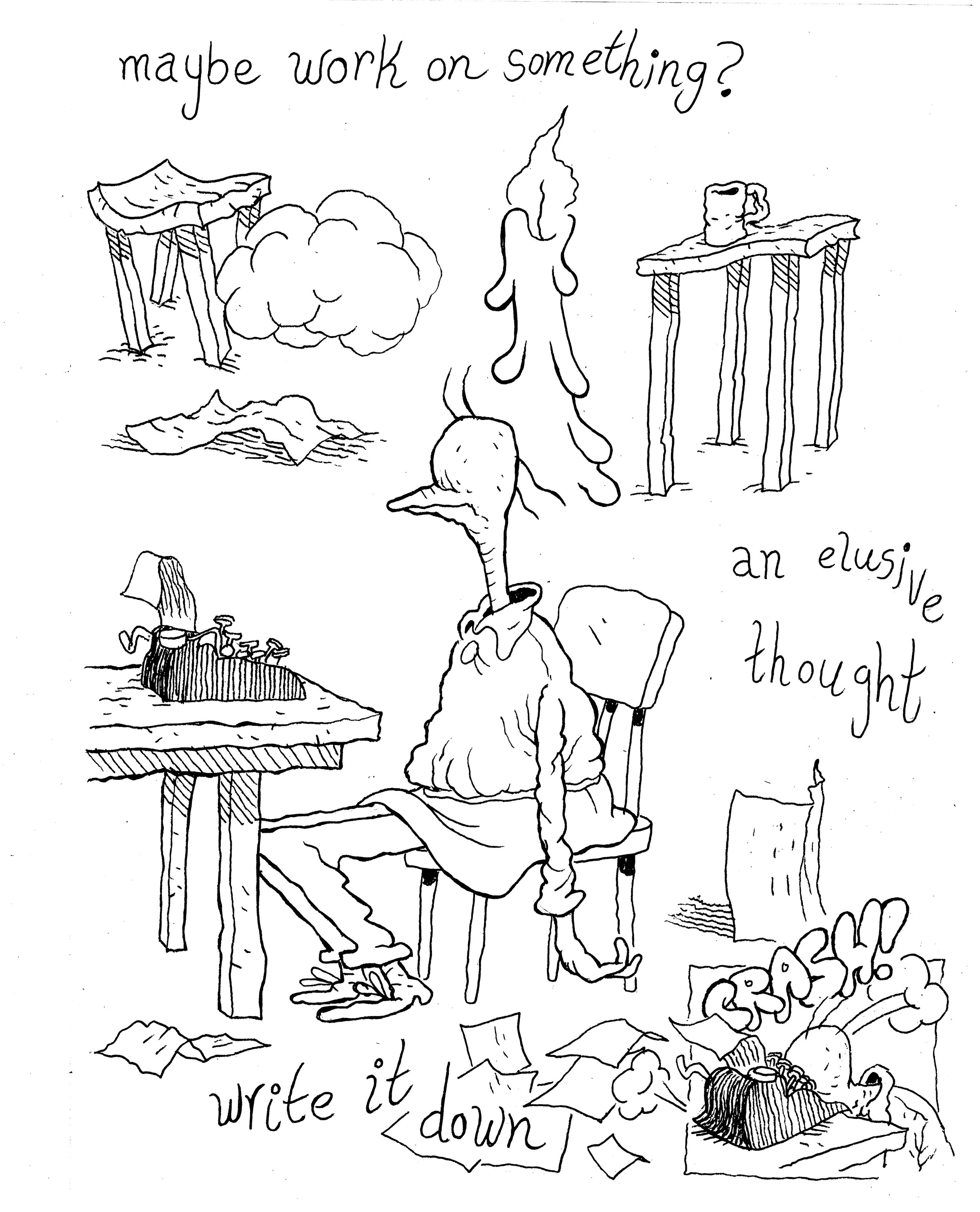

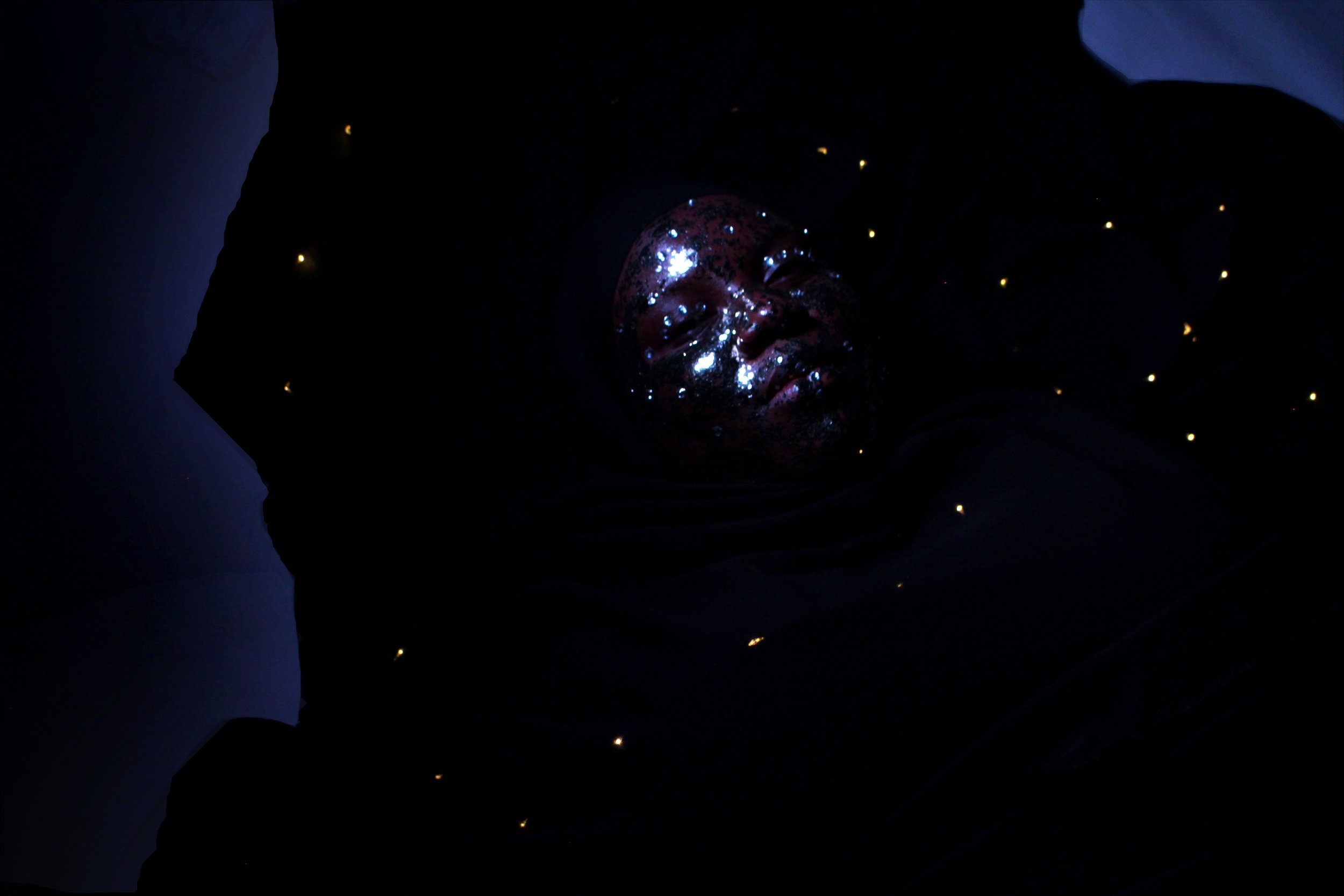

Enter the world of James Collier, one filled with birds in suits on their ways to work, night time walks and industrial environments slowly becoming overtaken by nature.

We chatted with James over email to learn more about his creative practice and inspirations. If you find yourself wanting some work of his for your own, you can DM him on Instagram.

Art by James Collier

Also Cool Mag: How did you get into making visual art? What mediums do you use most often?

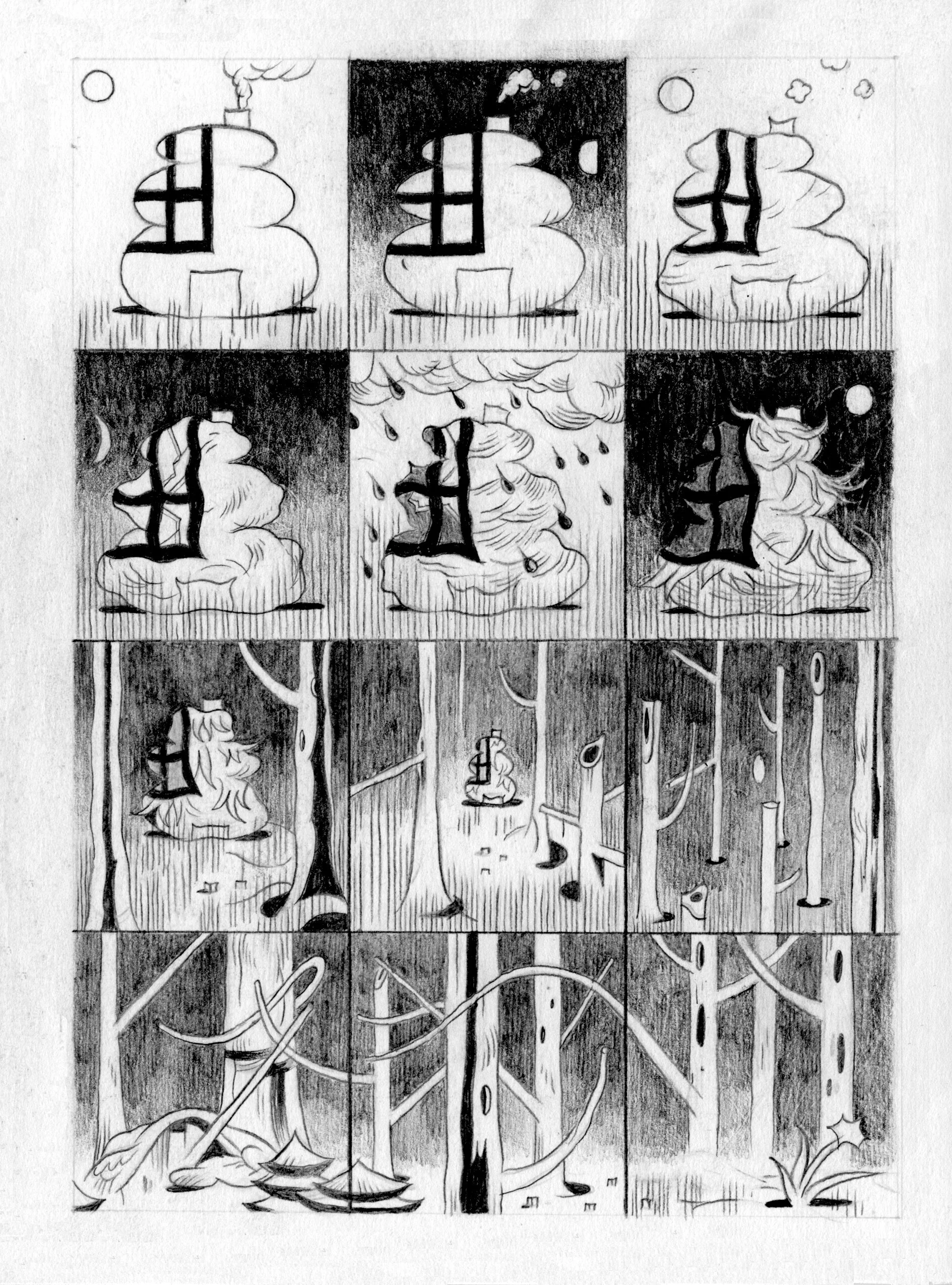

James Collier: Drawing and cartooning have almost always been part of my life. I learned how to read from Carl Barks' Donald Duck comics and grew up drawing all the time. My dad is a great cartoonist, and there were always comic books around which I would consume voraciously. I never really questioned art-making as a kid and thought making comics and drawing was just an intrinsic part of life, a way of making sense of the world. I stopped drawing altogether for a while though, and it wasn't until age 18 or 19, after a particularly bad mental health episode, that I picked it up again.

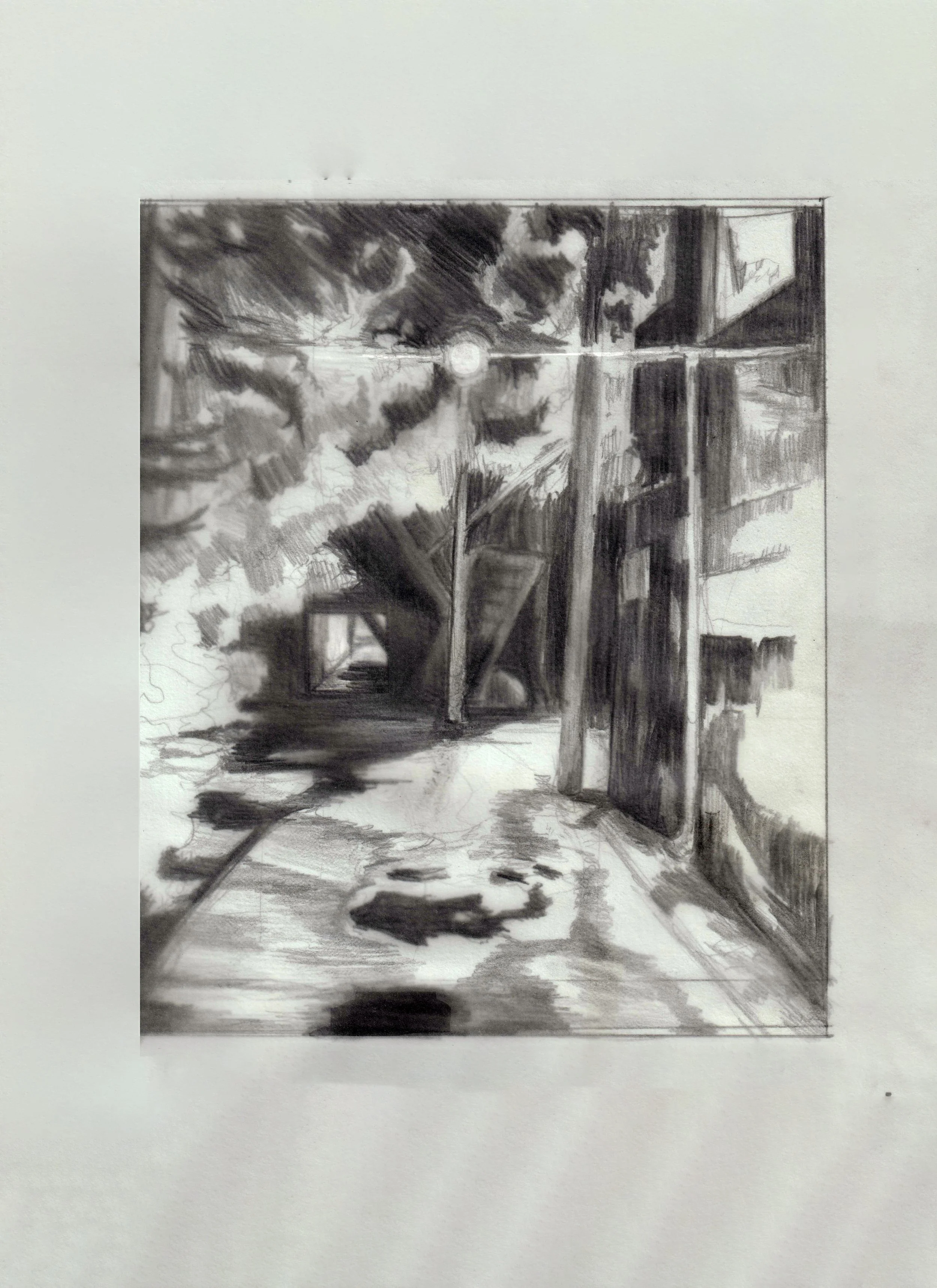

Mediums are pencil, ink, paper. Most of it is done in various notebooks with cheap pens or graphite on Stonehenge paper when at home. Though drawing is the most accessible, both cost and space-wise right now, I'd like to explore printmaking more in the near future.

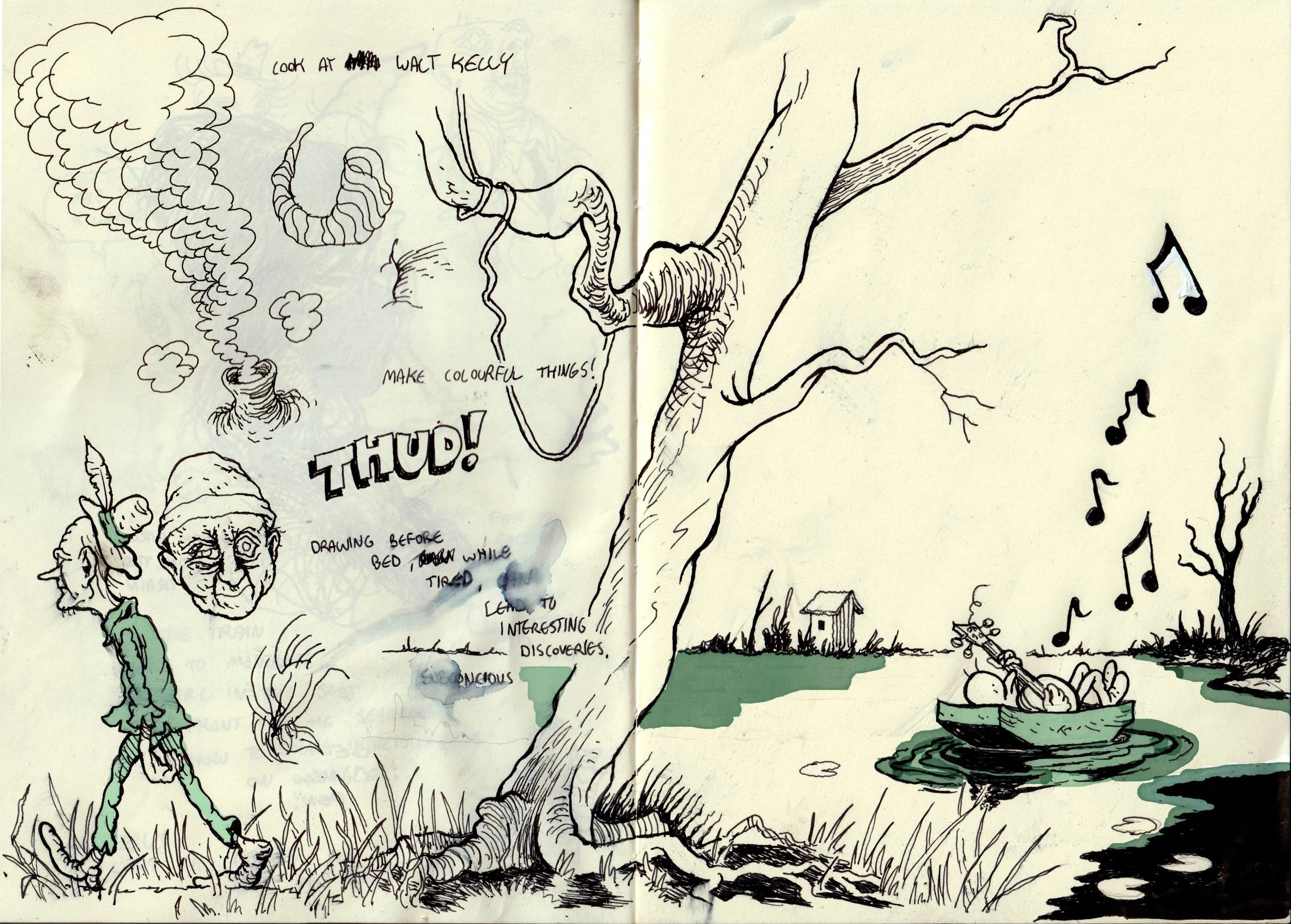

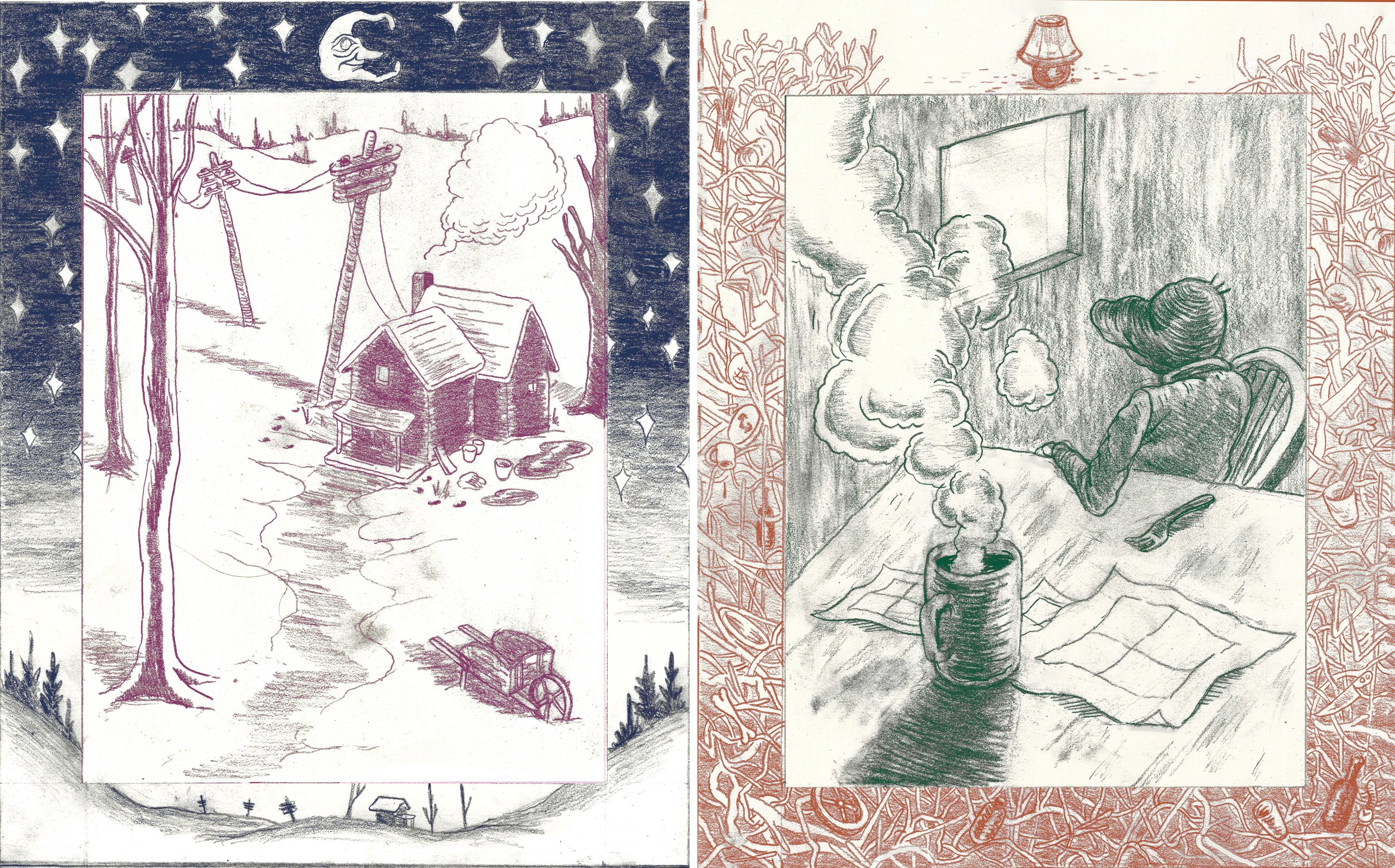

Art by James Collier

Also Cool: What kind of work and aesthetics were you interested in early in your creative practice? What inspires you now?

JC: Again, Carl Barks was a big one. There are a lot of people like Milt Gross and E.C. Segar who were/are big influences. Julie Doucet is continually inspiring – I can't wait for her new book, coming out in the spring.

I'm looking at the printmaking work of people like K the Kollwitz and James Ensor a lot these days. Herge, Joost Swarte, E.S. Glenn. The comics and drawings of Walker Tate as well. The comics and zines of U.K.-based artist Michael Kennedy are very inspiring. I've started looking at Walt Kelly again. I really like Charles Burchfield's paintings. I've also been looking at photographers such as André Kertész and Alfred Stieglitz.

Art by James Collier

AC: Where did you grow up? How did your upbringing shape your ideas about art and design?

JC: I grew up in Hamilton, Ontario. Hamilton is a city known for steel manufacturing. It's pretty grey, generally. Plenty of abandoned vacant lots, which I've gone back and drawn. There were also hidden bits of nature that you could get away to. There was an overgrown area known to my family as the "secret spot" that you could get to by canoe, as it was across the Hamilton Bay. I spent a lot of time reading and drawing there. There were also people around that you could collaborate with. My first printed work was with a local kid on my block, where we created a small photocopied zine entitled "The Guy who Never Returned" at age six. I don't remember what was in it, but we went around selling it on the street.

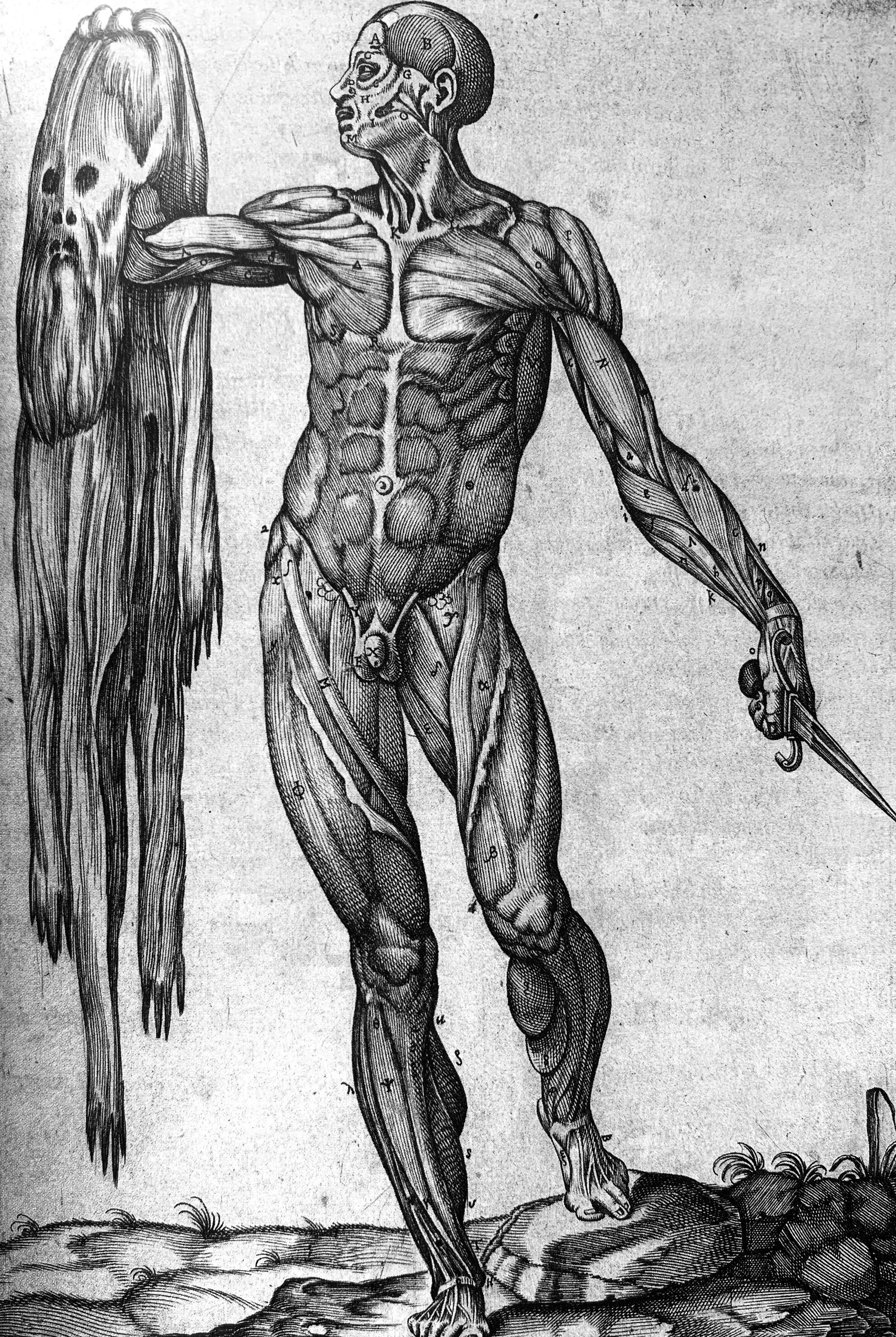

Art by James Collier

AC: How has your personal style developed over time? Can you tell us a bit about your bird characters?

JC: It's just the result of continually drawing in sketchbooks. It's a subconscious development, so it just changes incrementally over time. It's hard to track development.

As for the bird characters, while working as a window washer, I would be very tired at the end of the day and barely have time to make a few doodles and scribbles before bed. The birds emerged in my sketchbook one night while fatigued, and I've kept drawing them since. Related to this, I'm working on a comic right now about a duck with insomnia.

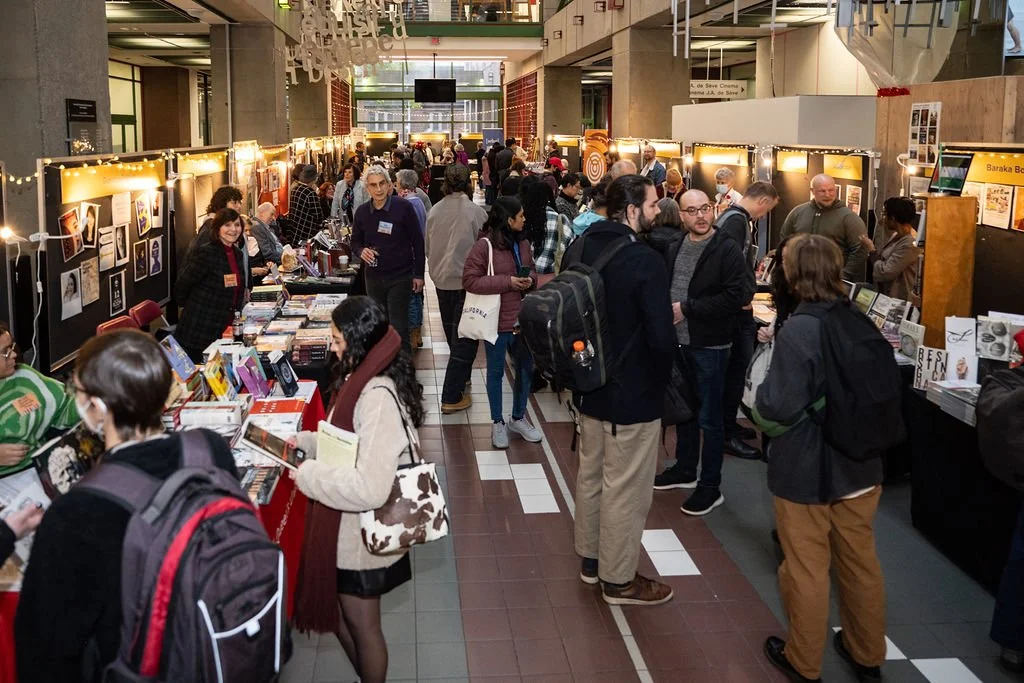

AC: Tell us a bit about the creative communities you've connected with and any artists/projects within them who inspire you.

JC: I'm lucky that I currently live around many talented artists. Being able to show things to people around you helps with not becoming disillusioned. I've found creative communities even in the world of minimum-wage work. When I was working at Metro Food Inc., as a greeter during the height of the pandemic, I had many discussions with the security guard about old animation and art history. Right now, I work at an art supply store with nice people who are very encouraging when I show them drawings.