Maya for Also Cool: How did you get into making music?

Lindus: I'm part of the internet generation - it's where my first connections came from. Sites like OiNK [Oink’s Pink Palace, now shut down], the first private torrent site, introduced me to some extremely nerdy internet stuff, which then expanded into music and music sharing.

I never really discovered much music through friends - most of it was through there - and the people on it listened to a lot of post-rock, like Godspeed [You! Black Emperor] and Explosions In The Sky - then everyone started getting into Burial’s end-of-the-world vibe. It was a time when the internet was a communication hub, but not as standardized as it is today. You had to crawl through lots of forums.

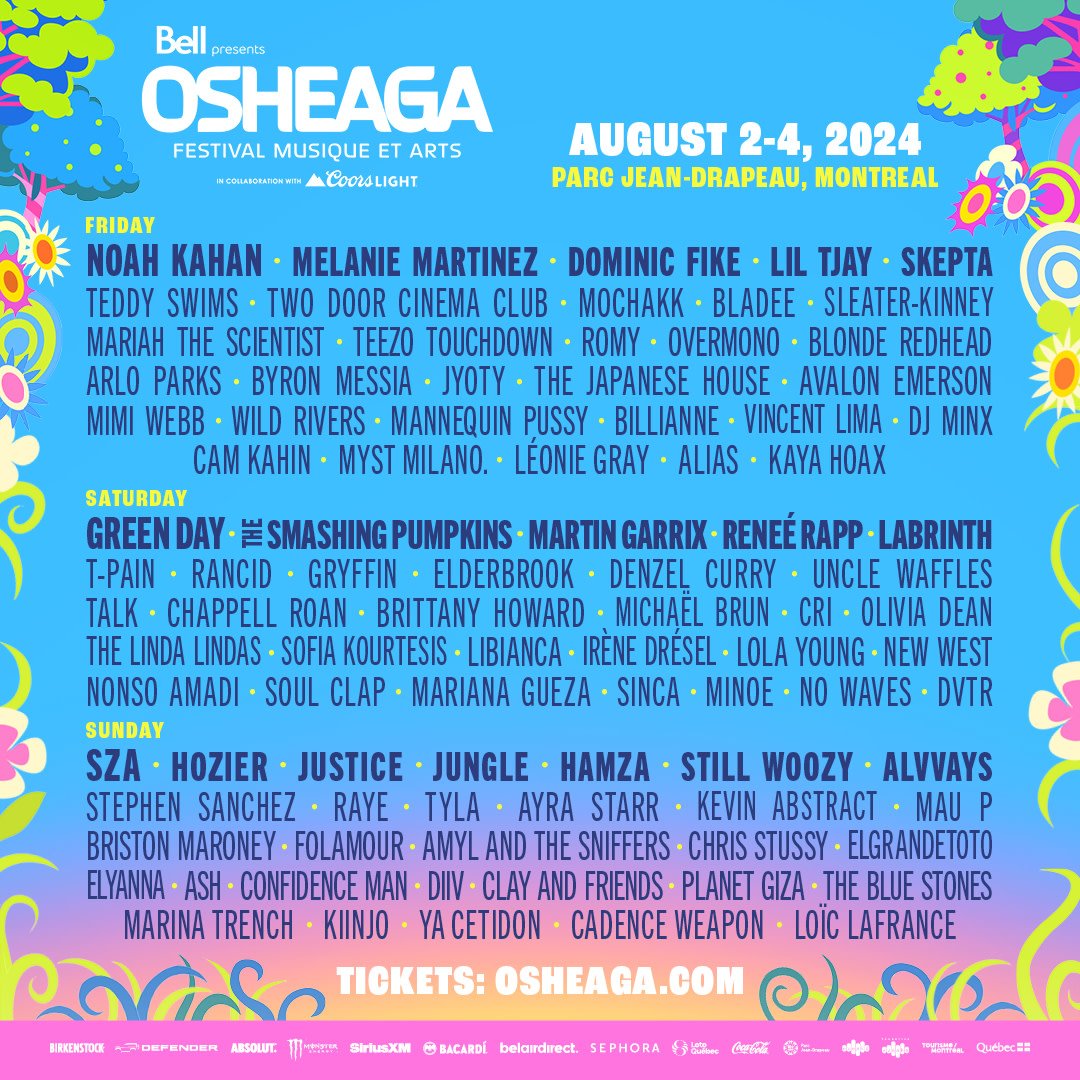

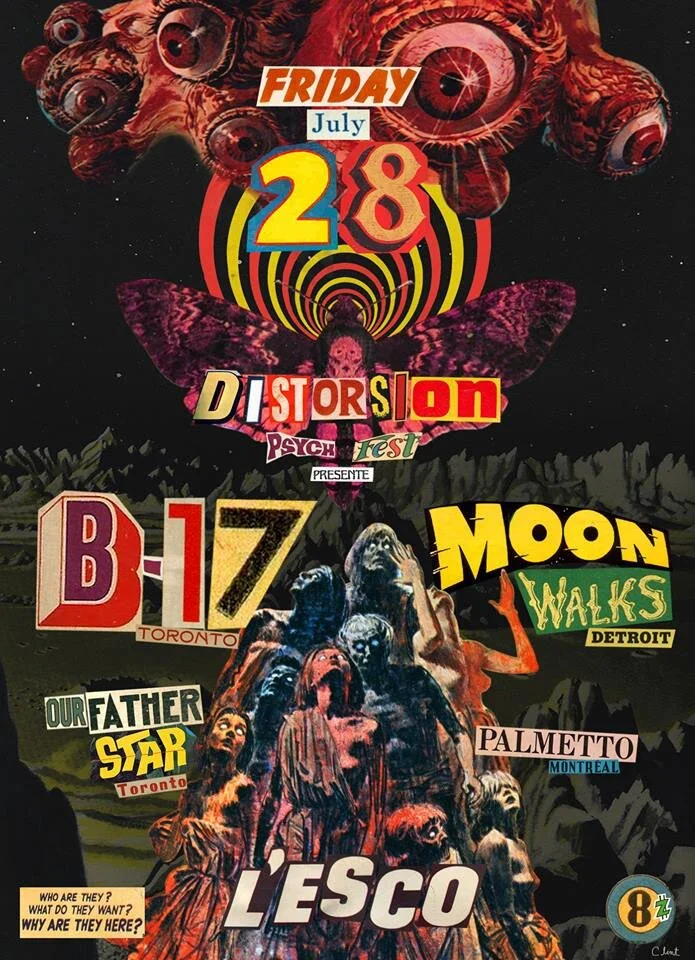

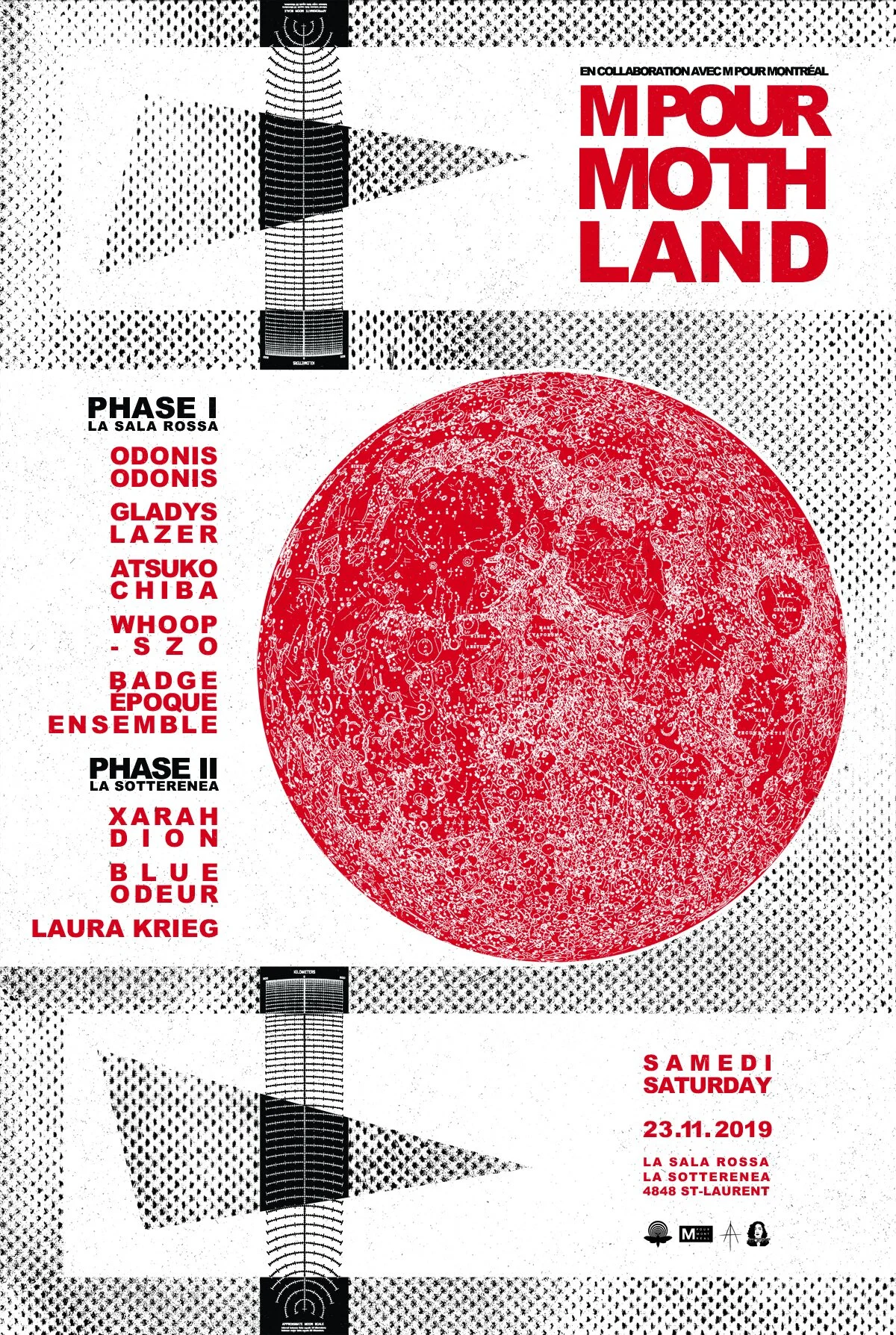

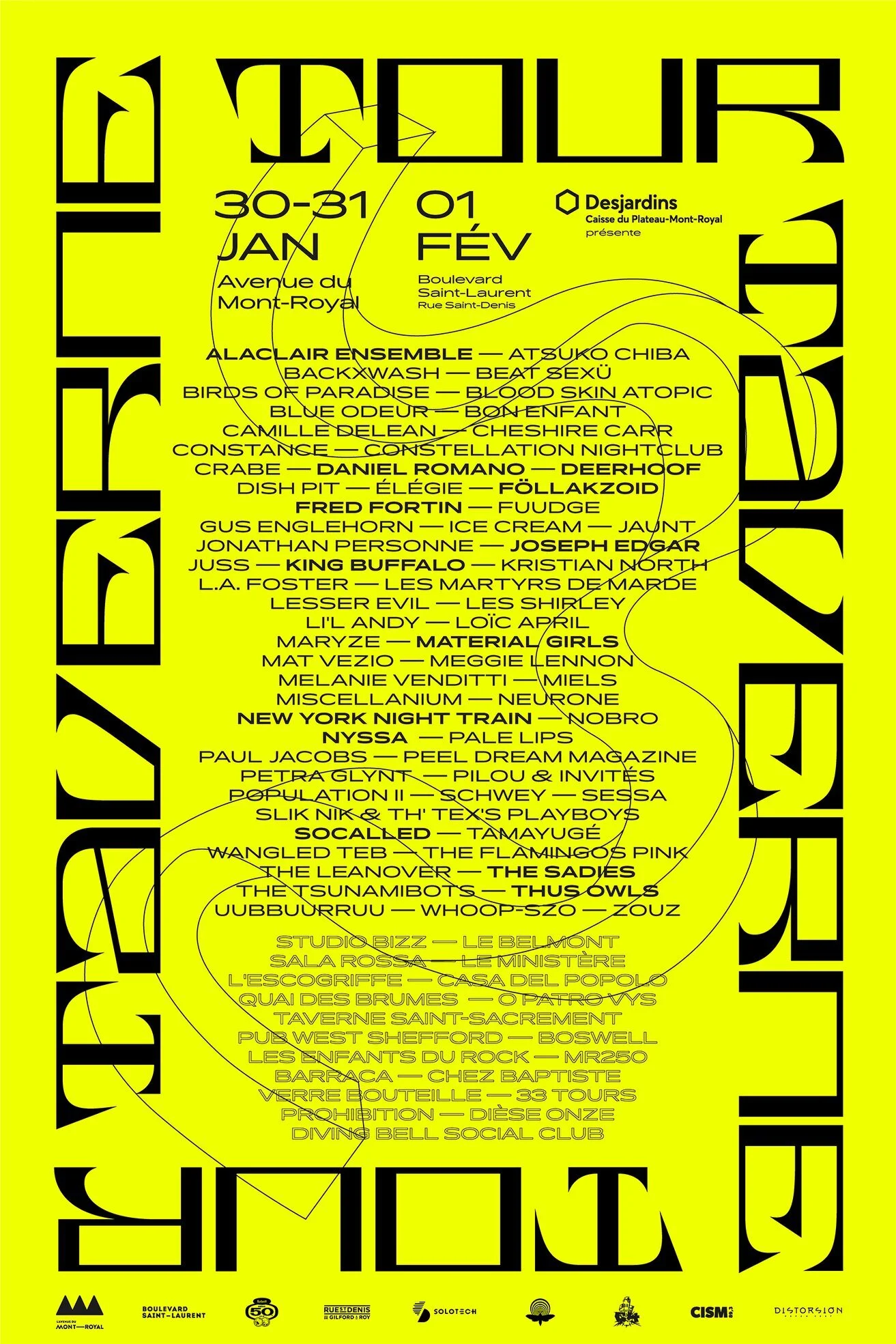

In 2010, MUTEK did a crazy showcase in Montreal. They featured Kode9, Spaceape, Flying Lotus, and Martyn - they were really on top of it that year. I started getting into dubstep and discovered clubbing through that - which in retrospect was a weird introduction to [the scene]. So my musical brain at the time looked like a mix of dubstep, psytrance, and all the Montreal post-rock bands like Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Silver Mt. Zion.

Also Cool: When did you start producing your own tracks?

Lindus: There's something about the world of dance music where there’s a high chance that someone who is consuming it is also participating in creating it. Especially back then, no one was buying gear - we were all making beats on the computer. There was a sense that anyone could try it. Lots of people downloaded the free version of Fruity Loops [FL Studio] and tried their hand at making music. That was when going to parties and making music started to overlap for me. I began making loops and sharing them online - before Soundcloud became so popular, people were using other platforms, like Myspace.

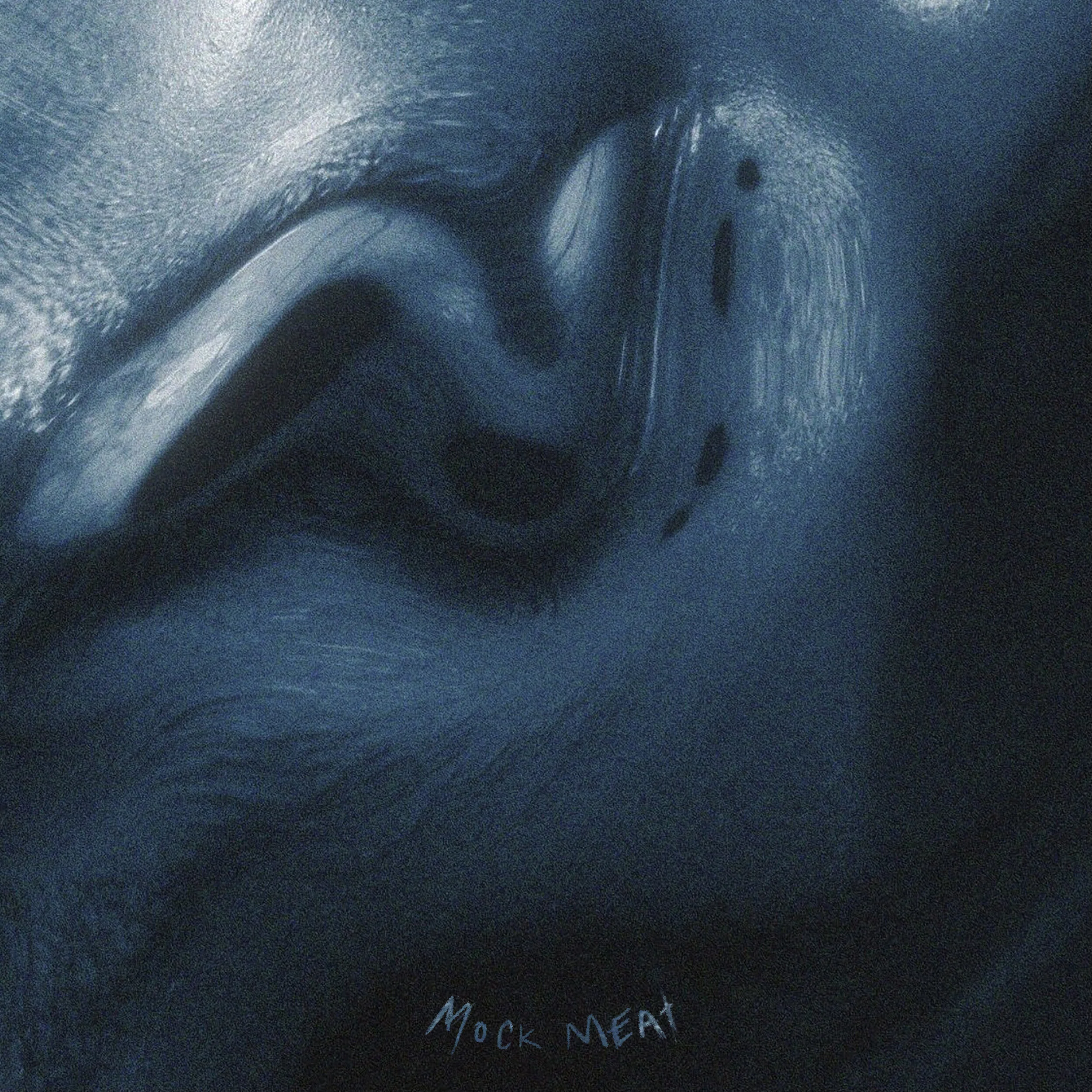

AC: Your write-up on the record describes a melancholy night at Stereo - do you have an emotional connection to that nightclub?

Lindus: Around 2011, there was a split in the scene - something broke at a local level, where what was originally supposed to be about music started having social consequences.

People started going into totally different scenes - some went from dubstep to bro-step, and some people realized they needed something new. A notable transition track was Joy Orbison's Hyph Mngo - it's deep, it's physical - like dubstep - but it sounded new. So a lot of dubstep heads transitioned to house and techno, myself included.

At one point people started hosting parties at this place called Velvet. One time I showed up with my roommate - we were like 18 or 19, just these awkward guys who went to these parties they found a link to online. When we showed up to Velvet, we got bounced - the bouncer actually pretended that we got the wrong address.

To me that was a sign that something in the scene had changed. The people putting on those parties were making a kind of shiny house music that was becoming really popular at the time - and all of a sudden these new venues would check you when you came in. That was totally unlike the [more relaxed] dubstep parties. At that point, it was a departure from the [underground] scene - it became more corporate. There was a car brand called Scion that put a bunch of money into these parties - I think that's when Red Bull also started getting involved - it felt really stale.

Maybe a year later, I went to Stereo for the first time, and it felt like a new community. It was like discovering a new part of dance music that I didn't know, because I didn't grow up with house or techno at all. When you're in there during the weird hours, like seven-thirty to nine [A.M.], you’d notice a special type of vibe - and the music made so much sense for the room.

That's also when I understood why people had to play house and techno in certain settings - you’re not going to play dubstep at seven in the morning when most people in the room are tripping. I tied the utility of the music with the scene and the space - and suddenly things made sense for me.

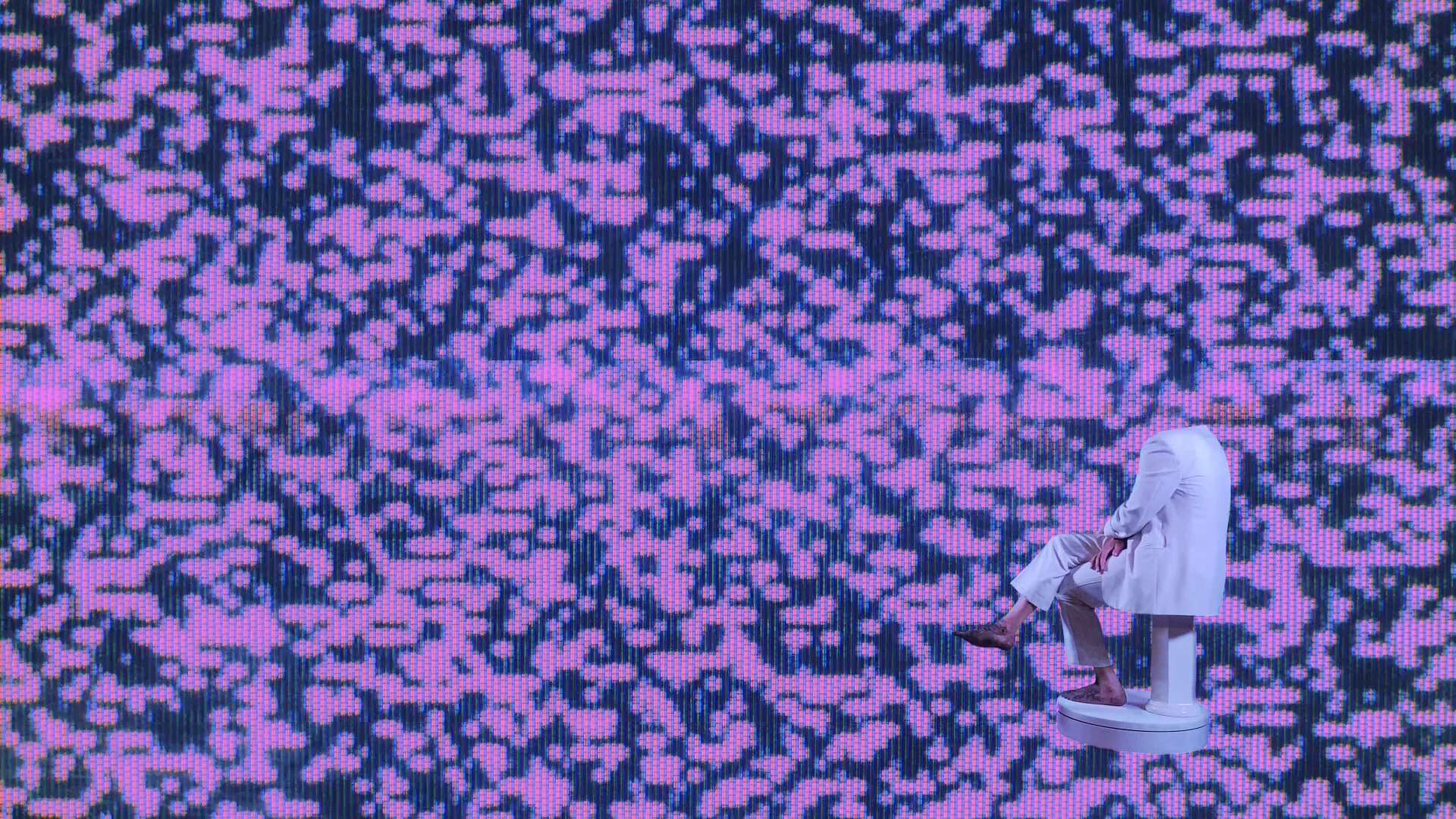

Then I just kept going. I definitely went to some weird nights. I saw Solomun there, which made me realize, “wow, they can really pack it with bros,” then I went to CLR Chris Liebing nights, where everyone was dressed in black and the music had really clean and crisp production and sounded super mechanical. I also went to see Danny Tenaglia and other house classics there - and those nights were great. It felt like I was entering into dance music history.

AC: How do you think SoundCloud affected the development of underground music culture - and the politics of it?

Lindus: Form became really important. I usually think of the Low End Theory stuff [the experimental club night responsible for Flying Lotus’ rise to fame, among others]. When that album came out, it was just at the beginning of the Internet. Everyone picked up on the formal characteristics of it - like the sidechaining, the pads, and the unquantified beats. Because of the Internet, like a week later, people from Sweden were copying those beats. Music felt really decentralized. You could also say democratized, because there were more people taking part in creating [these new genres].

With dubstep, there was this messianic thing. There was this vision of a scene in the UK - and with me being far away in Canada, experiencing this new genre from the UK felt full of promise. It didn't have anything to do with the formal characteristics of the music - it was more about the vibe, the projects, the communities. When people started getting good at Ableton and making really quick clones of beats, it made it hard to situate the music and sound within a scene. You no longer knew who to look to for leadership. Now it's easy to connect with a lot of people online and you can build community through the online medium.