Nabihah Iqbal On the Art of DJing, Knowledge Sharing, Mentorship and More

Nabihah Iqbal by Joseph Hayes, via the artist’s website

A virtuoso and undeniable taste-maker, London-based artist, producer, curator, broadcaster, and DJ Nabihah Iqbal says she could have never imagined the impact that her finely-tuned ear would have on audiences across the world. After extensively touring her 2023 album DREAMER for the last 18 months—all while igniting dancefloors in between—the globetrotting Iqbal reminisces watching people relate to her music as the “most incredible experience” of her musical tenure.

“I was reminded of the power of live music one night while in Minneapolis at 7th Street Entry when I left the stage feeling better than going on. I was feeling ill and tired that night, and just having a sense that it wasn’t going to be a good show. But I was met with the most beautiful crowd who had such good energy, so much so that I actually got emotional on stage. Though it was a smaller audience than others I had seen on tour, [the show] just did something to me that I had never felt before.”

Joining our virtual call from Upstate New York, where she is currently crafting a string-quartet composition, Iqbal’s warmth and candor are no match for the fuzz of our Google Meet signal.

Iqbal tells me the classical commission marks her first time working with multiple stringed instruments (apart from her signature polka-dotted electric guitar) and has introduced a welcomed challenge to her usual creative process.

“Even though I composed all the parts on [DREAMER], this is the first time I’m working with instruments I’ve never played before, like violin, viola, and cello. I’m normally thinking more about the relationship between the individual instruments when I’m writing my own music. But in the case of string instruments, you can’t just play a chord, there’s a lot of movement.”

In having to think outside the box, Iqbal teases that she would love to incorporate a string ensemble into her next album, which she says will be her next project once she wraps this musical residency.

When not serenading listeners with her atmospheric post-punk-influenced dream pop, Iqbal also moonlights as a DJ as a resident on NTS radio. She has graced the stage at Boiler Room, LAB LDN, Sacred Ground, and The Lot Radio among others, as well as clubs from coast to coast. As a crate digger with a background in ethnomusicology, Iqbal’s sets deliver top selections spanning genres such as Funk, Soul Jazz, Afrobeat, Dub, Disco, and more.

From being brought to tears by a Shakuhachi flute player in Kyoto, engulfed in the spiritual trance of a Sufi percussion circle in Lahore, and stumbling upon a polyphonic ensemble of Booboo pipe players on a beach in Sierra Leone, Iqbal gratefully credits her expansive palette to experiencing the role of music in different cultures around the world.

Though musicianship and DJing occupy different notches in Iqbal’s artistic belt, she says their influence on one another is indisputable.

“When you love music, you just absorb so much of it. What I create is a product of everything that goes into my brain. The amazing thing about DJing is that it really helps you understand more about the human relationship to music. It’s been there since the start of time, people moving their bodies to sound. It’s a primordial thing, and so much more than just playing music for people to dance to. It’s about taking people on a physical, spiritual, and mental journey,” explains Iqbal.

“When I watch more senior DJs, people like Moody Man, Gilles Peterson, or Benji B – they’re way more in tune with what DJing is and it's such an amazing experience. It’s what I aspire to cultivate. I love playing all kinds of different music with no boundaries – it’s all about how it makes you feel. The only thing is, it has to make you dance!”, she laughs.

Nabihah Iqbal DJing at NTS, via Friends of Friends / Freunde von Freunden

More recently, Iqbal had the opportunity to step into a musical leadership role at the legendary Abbey Road Studios in her hometown. Growing up near the St. John’s Wood neighborhood of London as a lifelong music enthusiast, Iqbal’s dream to explore Abbey Road Studios came true when she was selected to mentor a younger artist as part of its Amplify program.

“It was such an exciting and special experience to be recognized by such an iconic studio as someone who could come in and play the role of mentor. While the internet has democratized music and knowledge sharing, and the industry is starting to move in the right direction, I still feel like there isn’t enough acknowledgment of women producers,” she says.

Motivated by reinforcing the importance of reciprocity and encouragement in musical dynamics, Iqbal said she and the studio audio engineer, Seth, were happy to take the backseat and let her mentee Emily drive their recording session.

“For her, it was a lot of first times: first time in the studio, first time using professional gear, first time using her voice. I really wanted her to feel like she was leading everything that day," adds Iqbal.

Whether in physical or virtual spaces, Iqbal is committed to fostering inclusivity across all levels of the industry: “I think there needs to be more space made for goodwill rather than territorialism. The whole point of music is sharing. Without it, music wouldn’t exist at all.”

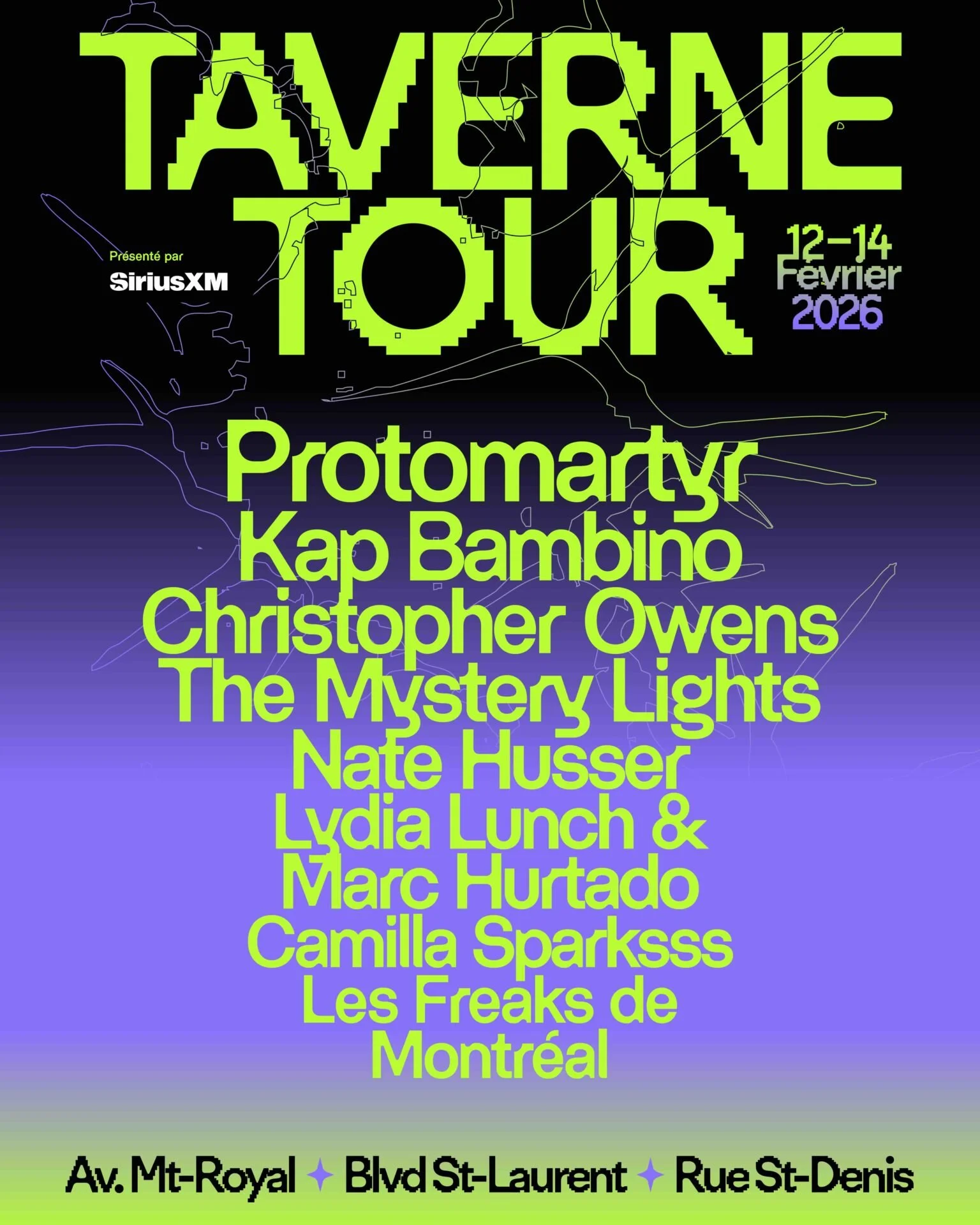

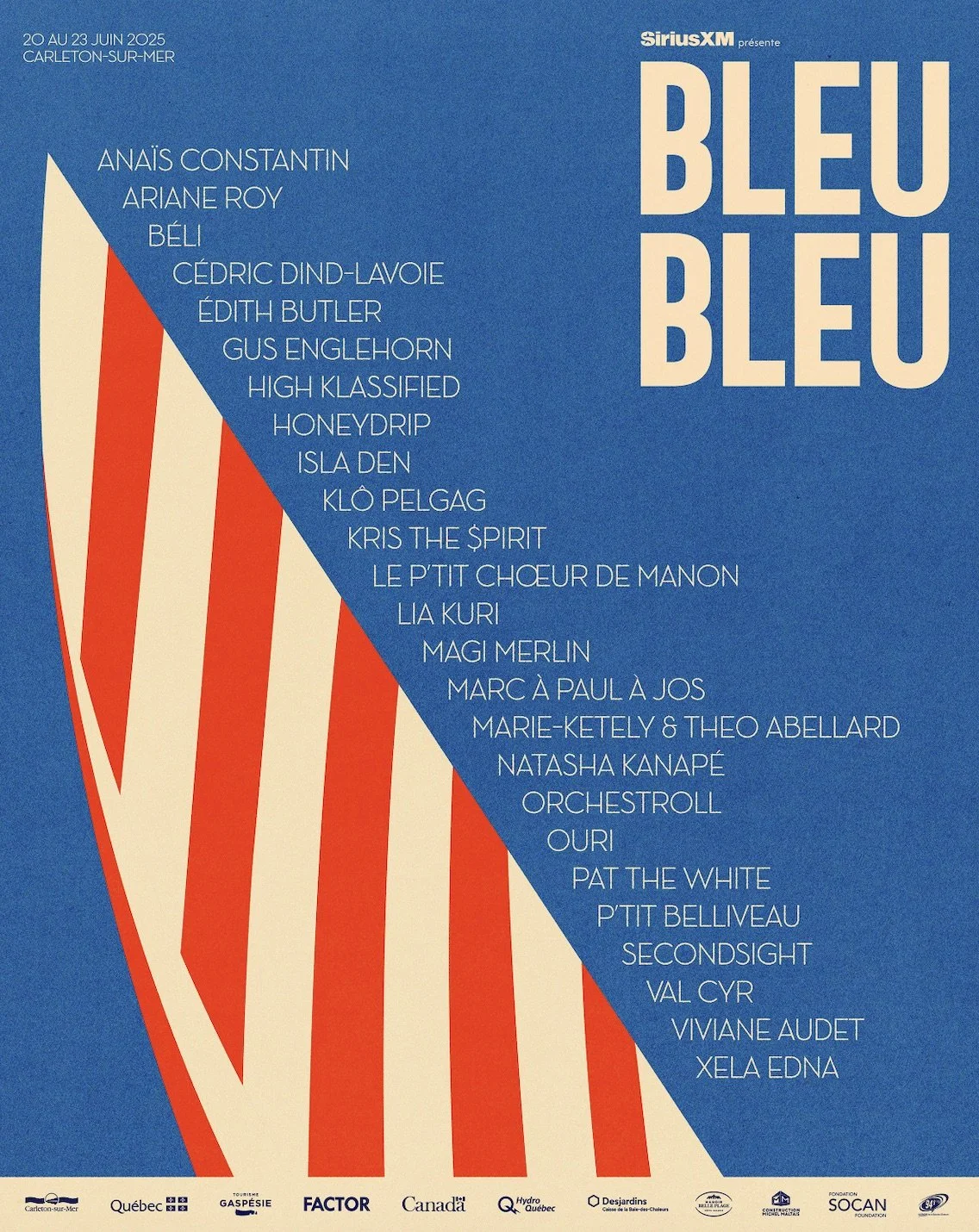

With musings for a new record forthcoming, Iqbal is set to tour in February and March supporting American singer-songwriter Sharon Van Etten. In the meantime, she is in midst of a DJ stint between NYC and Canada. Her tour will conclude in Montreal, where she will headline Also Cool’s first show of 2025 on January 25th at Le Système. Iqbal’s DJ set is not to be missed, as well as those from Also Cool Co-Founders Malaika Astorga (flleur) and Zoë Argiropulos-Hunter (Lamb Fatale). Early bird tickets are sold out! Get your second tier tickets below. See you on the dancefloor!