Bearing Witness: Domestic Violence and Working Class Women on TV

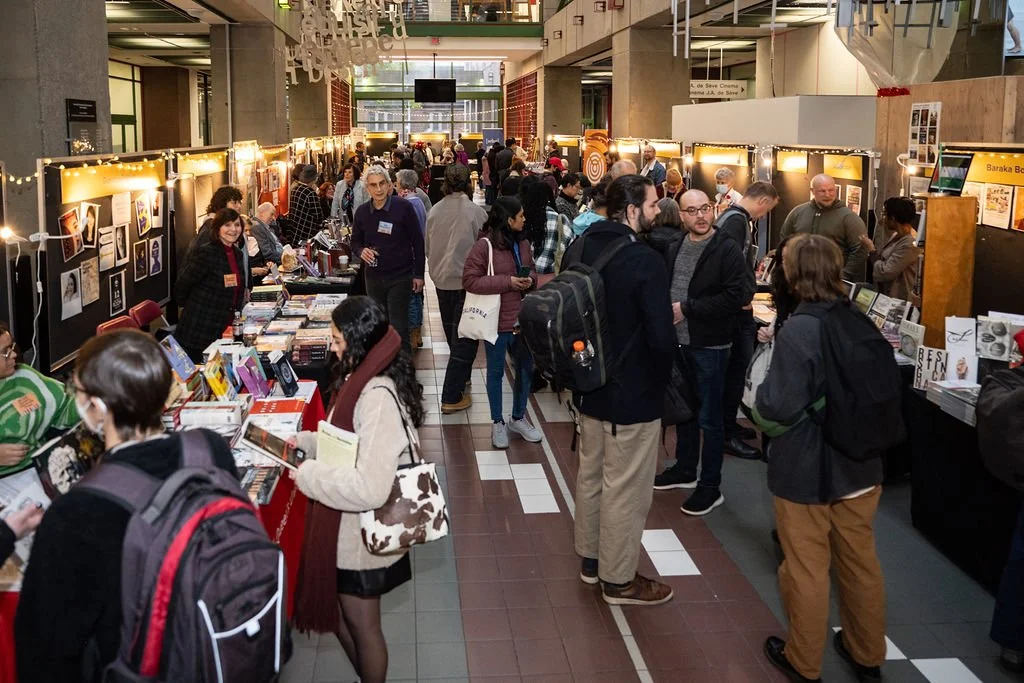

Recreation of a still from Can You Hear Me?, visual by Olivia Meek

Editor’s note: The following essay explores several themes that readers may find distressing, including domestic violence, sexual assault and police violence. Reader discretion is advised. Supplementary resources are provided at the bottom of the essay.

It isn’t revolutionary to see domestic violence on television. Quite the opposite — violence against women is too often an easy plot device to further a narrative, brushing over the real impacts of violence in a relationship. To see a series deal head-on not only with the dynamics of abuse, but their ripple effects in a community, is truly rare.

I had no idea what I was in for when I stumbled onto French-Canadian dramatic comedy Can You Hear Me? (M’entends tu?). Based on the description and the image, I thought, Oh, here’s another series about young people surviving in a big city. That’s a genre I like.

But Can You Hear Me? is hardly a new Girls or Insecure. The story of Ada (Florence Longpré), Fabiola (Mélissa Bédard), and Carolanne (Eve Landry) is an honest – and sometimes hard to watch – portrayal of the everyday negotiations involved in surviving when you’re young and poor.

When we meet the girls, Fabiola is working at a restaurant, caring for her mother and young niece. Ada is attending mandatory anger management sessions and occasionally trading sex for cash and cigarettes. Caro is living with a cousin and dealing with boyfriend problems.

As the first season progresses, we learn more about what has happened between Caro and her boyfriend, Kevan. There’s a rape at a party. Kevan blames Caro for her assault, and is physically violent towards her. The season culminates in Ada attempting to take revenge on Caro’s behalf.

On the big screen, portrayals of domestic violence are usually limited to thrillers about women’s revenge. Sleeping with the Enemy, Enough – these films typically end with the abused woman murdering her abuser. This trope not only perpetuates violent narratives, but it ignores the cyclical nature of violence. Normally in media, the act of violence a woman uses to get back at an abuser is celebrated, or at least plotted with her friends. “Can You Hear Me?” doesn’t let Ada off the hook so easily.

Season two picks up with Ada in jail and Caro back with Kevan. Once released, we follow Ada as she tries to win back her friend’s trust, and do the challenging work of supporting a friend in a violent relationship. That labour is complicated by the fact that each of the girls must also do the work of surviving.

Following her release, Ada is struggling to find her footing. Fab is now employed as a personal healthcare aide and is caring for her niece full time, navigating a complicated relationship with her sister, who is trying to stay sober. Caro finds a job in a bookstore, allowing her time away from her abusive boyfriend.

Other series have covered the topic of domestic violence. “Big Little Lies” is notable for its veracity and nuance in exploring the subject. But, as much in the media does, it focuses on wealthy white women’s experiences. The trope of domestic violence secretly occurring behind the doors of beautiful suburban homes is more about undoing our notions of the perfect family, or the American dream, than about the realities of violence. Rarely do we see a compassionate and complex portrayal of poor women experiencing violence. The vulnerability of poor and racialized women in the face of violence is either too invisible or too horrible to face.

While it doesn’t shy from the reality of violence and poverty, “Can You Hear Me?” finds pockets of joy in daily life. The excruciating scenes of trauma and pain are balanced with moments of levity. Outside their favourite dive bar, the girls smoke cigarettes and sing along to a song from a passing car. They laugh at the absurdity of life. Laughter is one way the women survive.

Most representations of working class experiences of domestic violence are delivered to our screens by the reality-documentary series COPS. The police ride-along mainly covers crime in poor neighbourhoods, focusing primarily on Black and Latinx men. “Domestic dispute” segments often involve police arriving at an apartment or trailer park, ridiculing both parties for causing a disturbance, and driving away. The aberration is not the violence, but the noise complaint.

Can You Hear Me? isn’t anti-carceral or pro-cop – rather, it acknowledges how dangerous it is for the abused person to call the police, and the way police escalate violence. When a neighbour calls the cops, Caro and Kevan both deny any violence. Later on when Caro calls the cops herself, Kevan is arrested, but the violence doesn’t stop — it gets worse. It’s a story about the failing of police as much as it is about domestic violence.

Without veering into didacticism, the series shows us the abuser’s playbook: isolating the victim from friends; groveling and using gifts to get their partner back; moments where things seem calm; lashing out violently when she finally feels ready to leave.

The moment someone tries to leave an abusive relationship is often the most dangerous. After Kevan is arrested, Caro eats dinner with her friends and her mother. A moment of joy. The history of violence is just below the surface of their conversation, bubbling up when Caro feels she can speak about her experience, but the women are laughing. For a minute, it seems like Caro is finally free.

But Kevan, as always, returns with flowers and a fist. It’s the kind of emotional blow one comes to expect from the series, which never lets its heroines (or its audience) off easy. As Ada’s counsellor tells her, “If Carolanne chooses to stay in a toxic relationship, you can’t leave it for her.”

Even when they disappoint each other, friendships are survival. Caro, Fab, and Ada are all trying and failing at breaking the cycles of violence in their lives. Chosen families break the abusive patterns passed down through bloodlines.

Caro’s mother, herself a victim of domestic violence at the hands of Caro’s father, seeks help at a women's shelter. This is perhaps the most novel of the portrayals of violence and its impacts on the series. The thriller’s focus on vengeance, the procedural’s focus on police intervention, and the drama’s focus on upper class women mean that domestic violence shelters are almost never shown on TV.

For a woman with money or connections, it can be much easier to escape to a hotel or friend’s house. By demystifying the shelter, the writers offer a new narrative and option for women, one that involves empowerment without perpetuating more violence.

It would be easy to make a preachy show about domestic violence, its causes, and the options available to those experiencing abuse. Can You Hear Me? chooses instead to tell compelling and true stories about the lives of working class women. In telling the truth, it exposes the narratives we are afraid to tell, opening up a world of storytelling we don’t get to hear.

Editor’s note: Below are several supplementary resources that pertain to the subject matter of the essay. We encourage all of our readers to explore these options, and to seek whichever form of help that they may need. Please exercise caution in using these resources on shared computers and devices.

ShelterSafe is a website that provides information to connect women and children across Canada with the nearest shelter for safety and support.

myPlan Canada is a free app to help those impacted by abuse with their safety and well-being. It customizes resources for a wide range of relationship abuse concerns in order to develop a safe and sensitive plan.

SOS violence conjugale is a Québec-based non-profit organization whose mission is to help ensure the safety of victims of intimate partner violence. SOS offers resources in over 25 languages.

For those outside of Québec or Canada, SOS offers a comprehensive directory of international resources. This directory can be found here.

Crisis Services Canada is a collaboration of non-profit distress and crisis service centres from across Canada. Their goal is to assist Canadians struggling with mental health and suicide.

The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime is a charity that ensures the equitable treatment of victims of crime across Canada. They have a directory of resources for those who have experienced sexual violence, domestic violence, and other crimes.