"Creating Space": A Conversation with Author Josie Teed

Josie Teed by Lauren Cozens

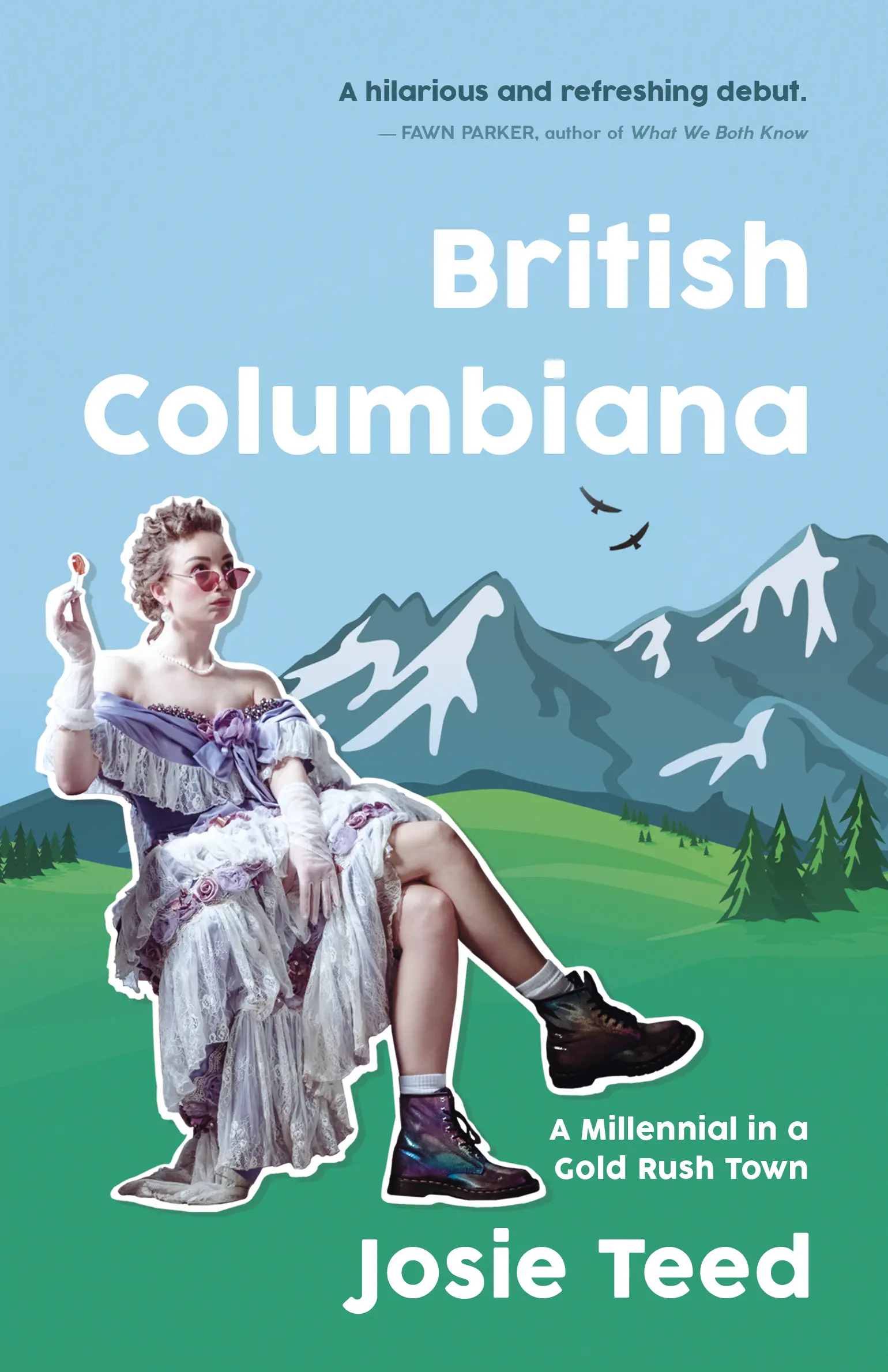

Josie Teed’s debut memoir British Columbiana, out now through Dundurn Press, explores a period of transition. After completing back-to-back degrees — a bachelor’s in art history and cultural studies at McGill and a master’s in archeology at the University of York — Teed accepts a job in the remote heritage town of Barkerville. Located in the Cariboo region of British Columbia, Barkerville showcases the nineteenth-century gold rush which led to the industrialization of the province. Teed works as an archivist and later as a heritage interpreter — that is, an actor who portrays significant figures from this era. Barkerville and the adjacent village of Wells, where Teed takes up residence, are composed of a diverse array of people — some of whom are settled there for good, and others who are just passing through.

People tend to not feel very present during transitional phases like the one that Teed undergoes in this memoir. However, Teed shows that transitions are often times of great experimentation, in which we parse through our desires and discard those that no longer serve us. I meet up with Teed on a mild spring evening to discuss the pursuit of belonging, the instability of friendships, the relationship between history and storytelling, and the complications of the memoir form.

We begin our conversation by talking about what motivated her decision to move to such a small, insular community after completing her master’s degree. Teed describes how she felt worn out by the pace of life in Montreal, where she did her undergrad, and was overwhelmed by having to encounter the same people every single day. After this period of her life, Teed really “just wanted to create space,” which is why she chose a school in York as opposed to a bigger city like London.

At the same time, Teed’s move to Wells was not so much an intentional decision as it was a leap of faith. “After I was done with York, I really had no one trying to get me to stay anywhere,” says Teed, “so I applied to a bunch of places through the Young Canada Works program. The only job offer that I had was from Barkerville. They were the only people who were saying, ‘you should come here.’ I also think that, on some unconscious level, I believed that it was important for me to go somewhere weird — just to be able to say later in life that I had been there. This idea is something I’ve definitely moved away from as I’ve gotten older.” In this memoir, Teed seems to oscillate between two desires — one to simplify her life and the other to revitalize it.

British Columbiana revolves around Teed’s pursuit to find community in Wells — where many people have politics which depart from her own. “In a university social justice space like the one I found myself in at McGill, there was this expectation that every interaction you have will be informed by your politics and that disagreements were meant to be approached in a confrontational way,” Teed explains, ‘but I learned very quickly that this would not really work if I wanted to have a comfortable life in a small community where people don’t always think so consciously about their politics. So the only thing I could do while I was there was lead by example and engage in gentle conversation when issues arose. I don’t know if that is how I would deal with the same kinds of situations now, or if it would even be ethical to do so.”

However, we also see that many of the people Teed connects with during this time prove to be inconsistent — and ultimately surprising — with their values. For instance, her friend Logan, who holds frustrating, retrograde ideas about gender roles, offers Teed valuable reassurance as she navigates her relationships with men. Meanwhile, Bobby, someone who Teed connects with on the basis of their shared political beliefs, cultural tastes, and educational background, becomes oblivious and — at times — unsympathetic towards Teed’s distress. “Logan was the greatest friend. She cared about me in a really active way that I hadn’t experienced in a long time,” Teed tells me. “But I felt so challenged by the differences in our beliefs and ways of conducting ourselves. Bobby and I felt relatively aligned, but she wasn’t available to offer me care — but maybe this is okay because that’s not what she wanted ultimately.”

British Columbiana by Josie Teed

The memoir also dissects Teed’s fraught relationship with men during this period. “I think living in Wells was the first time when I really felt like an object of desire in a continuous way,” says Teed. While Teed sometimes longs for the intimacy she witnesses between couples, she also seems to struggle when finding herself to be the recipient of romantic attention. She intermittently sets the intention of only cultivating friendships with men. She says to me: “When I was young, I think there was a big intimidation factor that kept me from being friends with men. I couldn’t help feeling that they were a cut above me. So I really wanted to lift the veil of mystification by actually spending time with men, but a lot of my experiences with men that I wrote about are really horrible! I just kept having these encounters where they really demonstrated a lack of character — at least in how they interact with women.”

I propose to Teed that perhaps men have a tendency to pigeon-hole women as sexual conquests or, if they do not see them that way, to display an almost cruel level of inattention. “Now I’m much more critical of them,” responds Teed, “but I don’t want to see people as incapable of showing me kindness. I also want to believe in people’s capacity to grow.”

While many millennial memoirs are rooted in the author’s interiority, British Columbiana conveys a distinctive sense of place. Teed represents not only the rugged geography of the region but also the way in which heritage sites like Barkerville function. In our interview, she notes that the town is “...owned by the government and perpetuates the state’s narrative of Canadian history.”

“A lot of people who worked there had a very different agenda from myself,” she remarks. “Barkerville was originally a mining town and they basically destroyed the area to build it. Something that I felt conflicted about was the minimization of this environmental destruction — the interpretation never really tapped into that stuff. It is also just a reality that a lot of funds are funneled into the upkeep of the heritage site and very few resources are left for anything else. I will say, however, that the summer I was working there was the first summer that they had Indigenous interpretation, and it was really interesting to witness the negotiations between the longstanding interpreters and the new Indigenous interpreters. I have my criticisms, but I also feel like Barkerville and its workers need support.”

Teed’s time at Barkerville ultimately challenges her passion for history, prompting her to realize that she is much more interested in how history is narrativized: “I really loved history, but sometimes you love a discipline, you enter it, and then you’re just there. With some space from academic work and research, I’ve realized that I’m much more of a storyteller.”

The memoir form tends to receive criticism for flattening out the people surrounding the speaker. Likewise, Teed felt the ethical complications of writing about real people. “In the beginning, I felt super guilty about writing this story. But one thing I tried to do was leave a lot of space for the audience to have their own judgements. I also tried to balance things out by truly exposing myself.” It is true that Teed is just as transparent about her own emotional hang-ups as she is about others’ and foregrounds the impact they have on her relationships.

This memoir also creates some of this ambiguity by representing the dialogue between Teed and her therapist Barb. Barb helps her approach problems from different angles but also brings a lot of texture to the narrative. “I think that the therapy sessions help create some distance from my initial impressions of some of my experiences,” Teed notes. “Through Barb’s interventions, these sessions function to prevent the reader from seeing my perspective as so definite. And I think they definitely soften some of my interactions.”

A recurring feeling that Teed experiences throughout the memoir is the sense that she is on the outside of other people’s stories: that life is happening to them and not to herself. As a result, Teed often finds herself wondering what kind of narrative her experiences will amount to — or fall short of. This can be a dissociative experience which increases the stakes of every moment and, I think, cuts you off from your desires. However, writing this memoir allowed Teed to revisit her desires from this time in her life and to feel “...less ashamed for having them in the first place.”

“I made a lot of decisions based on the kind of person I thought I was,” she states, “and a lot of my time at Wells was marked by thinking things and not expressing them. I realized writing the book that there are things I could have gotten if I asked for them. Expressing yourself is actually healthy and often yields results.”