Also Cool Mag Turns Two!

Lately, it’s felt like there’s not enough time to catch up on life, and at the same time like 2019 was last year. October 29th marked our second birthday, and in the spirit of pandemic time not being real, we’re celebrating fashionably late to our own party.

While it still seems unreal that this project has taken on a life of its own, we’re incredibly grateful for what it’s become. We still check every notification, freak out when we see someone wearing our merch in public, and are genuinely shocked (in the best way possible) when someone says, “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of Also Cool!” For a long time, this project only existed on our laptops, in our emails, and had barely broken into the real world, never mind the mainstream music and media industry.

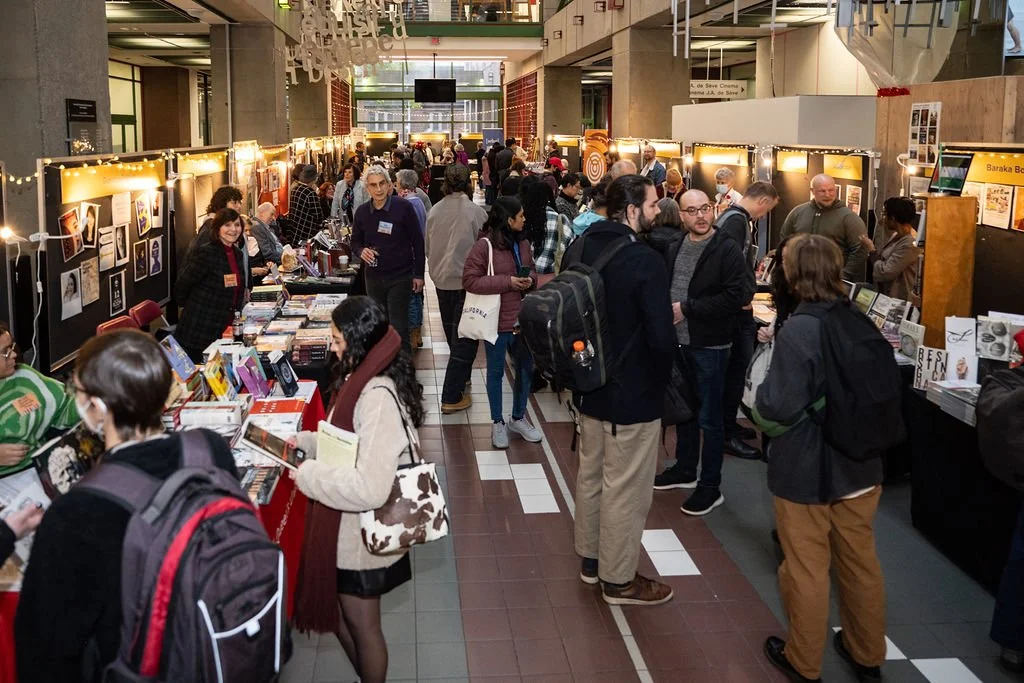

Despite another year of unpredictability, we are grateful for friends like you. We’re slowly starting to meet you all in real life at events or by happy coincidence out in the world. This project continues to evolve with our community, and we are so fortunate to share our achievements with people like you who believed in our values and philosophies from the beginning.

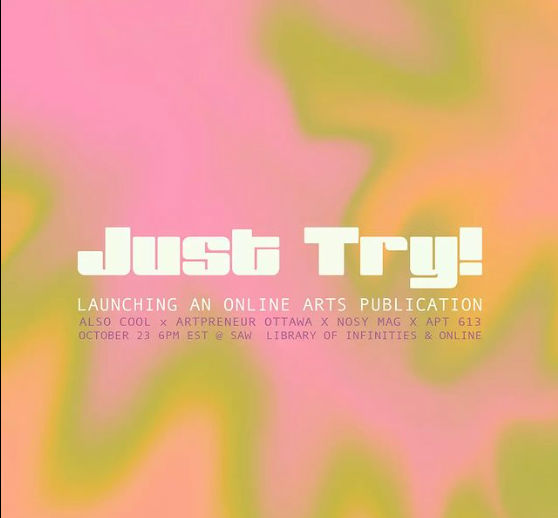

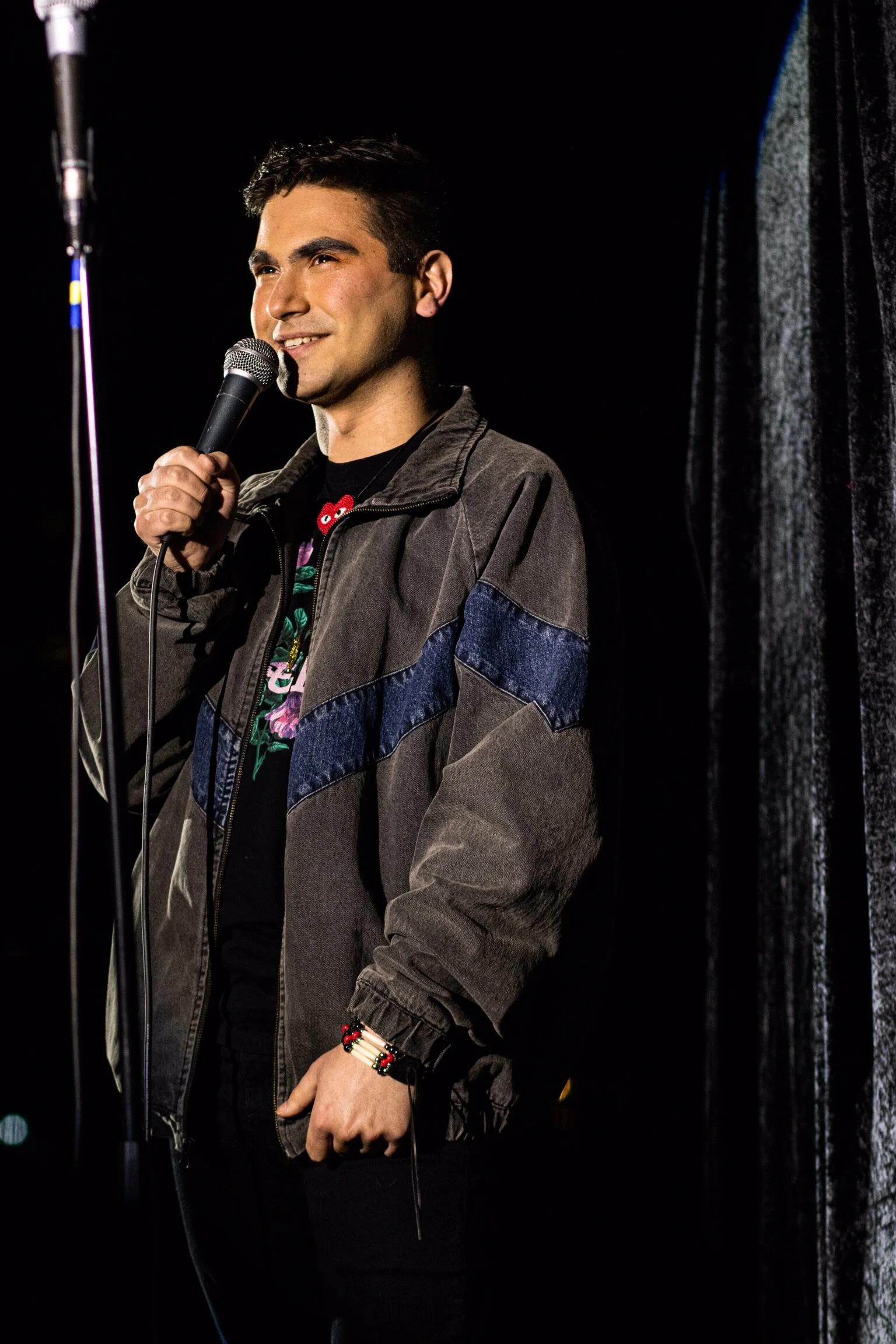

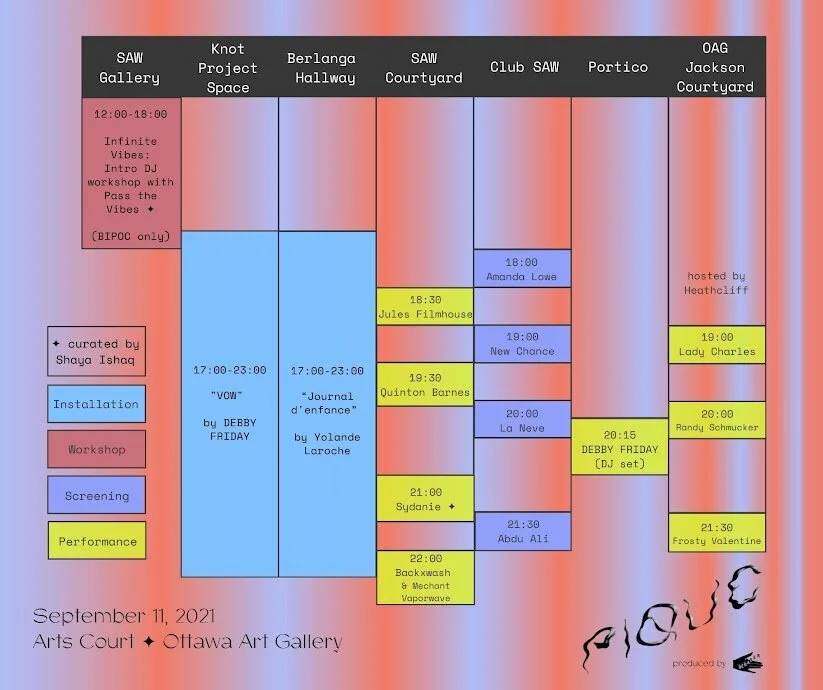

Some milestones from this past year include the launch of our podcast Also Cool Sounds Like on N10.as, starting our radio show on the virtual airwaves of FSR, being named as one of Montreal’s best magazines in Cult MTL, hosting panels with Fierté Montréal and Hip Hop You Don’t Stop, playing a live stream with Shift Radio, hosting an exclusive screening at SAW in Ottawa, working with the local legends at Mothland, covering FME in Rouyn-Noranda (after years without live music, RIP), watching our Co-Founder and Creative director Malaika speak at the 2021 edition of Artpreneur, and––of course––every interview, special feature, newsletter and meme dump in between.

Oh, and we also launched a Patreon, where we send our Patrons cute snail mail letters, personalized playlists, and more! Sign up here <3

We feel very fortunate to be at a place where our publication can grow without compromise of its DIY grit and devotion to our community. We’ve gotten the chance to work and grow with so many incredible contributors over the past two years, and we can’t wait to keep expanding the team.

With that being said, we’re looking ahead to a bright future and hoping to take our project to the next level. Lately, we’ve been asking ourselves, What do we need in order to grow? What does our community need from us? and, most importantly: How can we share all this, and our platform, with you?

It goes without saying that the last two years have been demanding, because of you-know-what and the trials and tribulations of life in general (we will never hold back from telling you all that this publication is run by real people who all have day jobs, on a volunteer basis). Regardless, this project is what has kept us going in dark times, and what has helped us believe that people really do care about the creative community that surrounds them. People want to love the city they’re in and discover other creatives who are just like them, and if we can have a hand in helping with those connections, we will do everything in our power to keep that DIY spirit alive.

We’re so excited about planning for this next era of Also Cool, and will hopefully be seeing you on a dancefloor very soon. As always, if you want to get involved in some way, or just want to chat, we’re an email or a DM away.

Anyways, what we’re saying is that knowing that you all still pick up what we’re putting down is a tremendous gift, and it is our honour to keep this platform enlightening, inquisitive, and cool.

Until next time,

XOXO Also Cool

![AI-generated image for “from [ ] [ ] of what remains, With little else [ ] [ ] who complains?” by Matthew Whitton. Photo courtesy of artbreeder.com](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5da4c68a227a253ac912f3a7/1629286297396-RLX4JXFW9XK4E2XWSCRO/Matthew+Whitton.jpeg)